Election Commission Appointments: CJI as “best man”? - Former CEC’s disagree

Though the fate of the issue of appointments to the Election Commission has been sealed, with the Supreme Court reserving its order, former Chief Election Commissioner’s reflect on whether the route should follow convention or reform

The Election Commission of India (ECI), a permanent constitutional body, has been making headlines recently - on account of hearing in a 2015 public interest litigation (PIL) before Supreme Court which has deemed the current system for appointing members to the ECI “unconstitutional”. Supreme Court’s comments on the appointment of the Election Commissioners & whether there is “hanky panky” involved in the process may not be the most tumultuous news of the week that was, for it also mulled upon the possibility of introducing the Chief Justice of India (CJI) in the committee that appoints the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC). Interestingly, the five-judge bench flagged the need for “neutrality” in the process of appointments in the constitutional body, adding that the selected person on the committee must be someone who would not “bulldoze under pressure”, essentially implying that the CJI would be a good fit.

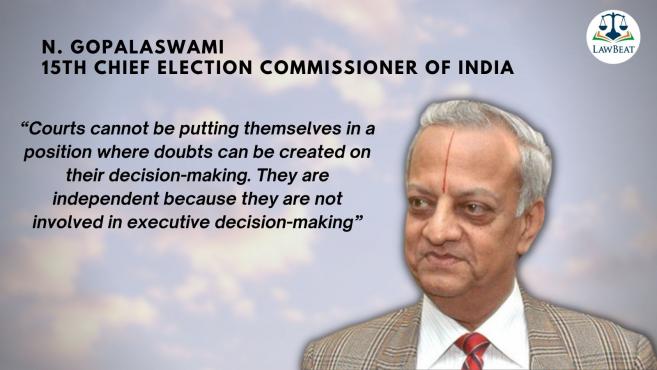

Former Chief Election Commissioner and Padma Bhushan Awardee, N. Gopalaswami (15th Chief Election Commissioner of India from June 30, 2006 to April 20, 2009) thinks that the process of appointing members to the Election Commission is "purely an executive function" and that it must be left to the Executive, for the proposal of espousing the CJI in the appointment process of Election Commissioners could cause fissures in real time. According to Gopalaswami, this would be detrimental to the majesty of the Supreme Court. He elaborates this by a hypothetical example of how a decision of an election commissioner, selected by a committee consisting of the CJI, among others could be under the scanner later. “If they become part of what is essentially an executive function, then at a future date, a situation may occur & it could be a great comedown for the institution”. Gopalaswami thrusted upon the aspect of the Supreme Court as being the “final arbiter of justice” in the country.

Achal Kumar Jyoti, who served as the 21st Chief Election Commissioner of India from 6 July, 2017 to 23 January, 2018 shed light on the system of appointments of the commissioners which has been continuing since 1951. According to him, there is “nothing wrong or untoward” about the decades-old procedure for appointments and the Union Government is quite a competitive authority to make such appointments, without any need for the Chief Justice of India to form part of the appointment committee.

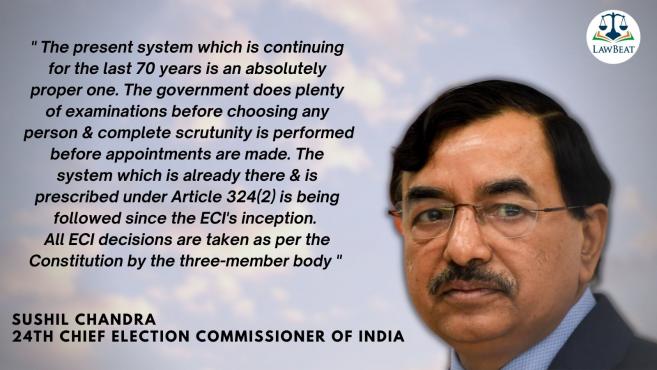

Sushil Chandra, the 24th Chief Election Commissioner of India (from April 13, 2021 to May 15, 2022) is of the opinion that the issue of appointments to the ECI already undergoes enough checks and balances and the system of appointments is sound. On whether the CJI should be part of the appointment committee, Chandra pointed out that the procedure which is laid down in the Constitution is a perfect one and there is no reason to change it.

The fate of whether the appointments which have followed a 7-decade convention need to be altered and if the CJI should be part of the appointment committee has now been sealed, with the Supreme Court reserving its judgment on the issue. However, the comments of the highest court, if taken at face value, reflect a heuristic technique of arriving at a solution to the slippery debate of whether the institution is partisan, whilst ignoring established principles and doctrines as well as stark examples of what really upholds “independence” in letter and spirit.

The election commission of India (ECI) has been a bulwark of democracy. Experts around the globe have called it one of the most “widely celebrated and trusted public institutions in India”, for it has administrated 17 national and over 370 state elections till date, fairly and without much ado. It will also be a fraught assumption to make that bolstering this massive task in the most populous democracy on the face of earth is an easy feat. Obviously, this has not been sans challenges, for the ECI as an institution, embarked quite a journey and survived the ups and downs in the early years of Indian politics.

Over time, its mandate and autonomy has only grown, however, there are plenty examples which demonstrate there is no one-size fits all for establishing the coveted “neutrality” in institutions. Take for example, the presence of the Chief Justice of India in the panel that appoints the CBI director and reflect on whether this contributed positively to the institution in any manner? The question may be an open ended one but when a solution is presented as the only one and judiciary is looked upon as the last hope, it may be an important one to pose.

After the 11th Chief Election Commissioner of India, MS Gill retired from his position, he joined the Indian National Congress & was handed a cabinet position. Though Gill was appointed CEC during the BJP’s short-lived term in 1996, it begs the two questions – firstly, is this what the ruling party at the time envisaged? And if it did not, would it have “preferred” to appoint a CEC with allegiance to the opposition? Secondly, how far can the string of neutrality be adjudged and what are the barometers upon which these virtues are tested? Are there any? Of course, the tussle between TN Seshan and then Election Commissioner Gill is another case in point. The Supreme Court has stated that Seshan was an honest CEC & his interview reflected that but at the same time, Gill's opinion of him is rudimentary? His interview to the media back in the day is telling.

Currently, the members of the ECI are appointed by the President to a tenure of six years, or up to the age of 65 years, whichever is earlier. They enjoy the same status and receive salary and perks as judges of the Supreme Court of India. While the case proceeded before Supreme Court, the Attorney General for India (AG) R. Venkatramani informed the judges who questioned how the appointments were being made that that the process was a “time-tested” one which followed seniority. “A panel of names is prepared for consideration of the Prime Minister and President. After consideration, the Prime Minister recommends one name to the President. That’s how the system works,” he said. To explain this convention, the AG went on to draw a corollary with the collegium system for appointment of judges & said that there existed no “trigger-point” as pointed out by the bench, giving leeway for the court to intervene. The Solicitor General of India, Tushar Mehta (SG) pointed to the court that though there may be “trigger points”, the question which required due consideration would be which one would be an apt forum to work on them, considering that “no one could get into another’s powers”. “There is an impression which has been made out that someone's presence has to be in the appointing authority who is not a part of the executive. That will mean rewriting the constitution,” the SG said, adding that both the judiciary and the executive were “equally sacrosanct" and equal organs per the Constitution of India.

This masterclass by the AG & SG on Separation of Powers before Supreme Court of India may have been short and subtle but the intent and message was clear – showcasing of constitutional boundaries and the manner in which the Constitution of India establishes functions – within well-defined frameworks.

Needless to say, it is always an opportune time to reflect on the Constituent Assembly debates and, in this context, even more so, for in the words of former chief minister of Kerala, K. Hanumanthaiah - “It is wrong to argue that few judges of Supreme Court are better than 400 Members of Legislature, duly chosen representatives of people….. Some people are prone to take advantage of difficult situations governments work under to raise controversies & to decry executive. To continually decry executive & legislature & to exalt judiciary is not doing service to either”.