Rising to the Bench: Abysmal Representation of Women in Judiciary & the Road Ahead

Introduction:

Since 1950, of the total 247 judges who have been appointed to the Supreme Court so far, there have been only eight women judges.

In the 25 High Courts of India, currently a mere 11.04 per cent of the whole, 73 women are sitting judges.

According to Vidhi Legal Policy Report, the lower judiciary has 27 per cent of female judges, the high courts near 11 per cent and the Supreme Court is close to 1 per cent. There is a reason for mentioning these statistics owing to a deepening concern of representation, gender inequality, and parity at democratically functioning institutions.

This paper sketches the present state of diversity and inclusion in the national pool of judges, and the remedial measures which are being taken to improve diversity and inclusion. The aim is to critically analyse the efficacy of these measures so far, and suggest new, hitherto unexplored measures to further improve diversity and inclusion amongst judges in the national judges’ community.

Gender Diversity and Lack Thereof in Judiciary:

The intrinsic case for diversity in judiciary (global and national) is a subset of the general intrinsic case for diversity. Gender diversity and inclusion in all aspects of human life is ethically regarded as precious and valuable. In other words, it is ethical to strive to secure diversity and maintain it, in every aspect of life, because that in itself is a right thing to do. Judiciary is no exception.

In any judgement, the role of the judge[s] is to render a cogent decision in respect of the dispute, conflict or a case which has been referred to. It has been consistently demonstrated that diversity generally tends to lead to better and guided decision-making.

Under representation and the “pipeline-leak”[1], which restrict women from reaching senior positions of power, clubbed with confidentiality clause of appointments worsen the situation. The greater breadth of experience, exposure, and sensitivity, that can be garnered from including gender diverse cohorts as judges, will thus account for better disposal of justice.

It was after 40 years of establishment, in 1980 that the first woman judge in the Supreme Court was appointed Justice M. Fathima Beevi.

As of now, amongst the 25 chief justices who head High Courts, Justice Hima Kohli is the only woman judge.

As opposed to 403 men, there are only 17 women senior counsel designates in the Supreme Court. Of the 27 sitting judges in the Supreme Court, presently there is only one woman judge. Of the 1080 sanctioned strength of judges in the High Courts, 661 posts are occupied and 419 are vacant.

These statistics published in the public domain increase the visibility of progress and push the initiative to a positive direction. It is however to be noticed and maintained, that more meaningful progress should be accrued when assimilating a revolution in the composition of judiciary.

It cannot be missed that it is a collective responsibility to increase the participation, inclusion and performance of diverse groups, as that aids in providing better results and maintaining equity. While the numbers are encouraging, they still are not as promising as they should be to ideally strive for a gender equal space. The common phraseology of pale, male and stale should not be applicable to the judiciary in India, as we should achieve a level of commonality which has an equitable number of women in positions of judgment and respective power.

Good solutions to the diversity problem in judiciary should ideally attempt to undo the effects of the causes, if not the causes themselves, of the lack of diversity and inclusion in this context.

Women have been conveniently excluded, which could have a branching to reasons such as lack of role models, inconvenient working models, job security during maternity periods, and the like. The under-representation of women in judiciary is well-documented.

The myopic focus on the under-representation of women alone risks shifting the spotlight away from the fact that under-representation on the basis of any intrinsic human trait, be it gender, race, ethnicity, or any other factor, is concerning because it tends to militate against the benefits of diversity. If there is to be a fairly comprehensive solution to the diversity problem in judiciary, it is necessary to devote equal attention to the fact that social cohorts other than women too continue to be under-represented.

Western International Scenario in the Present Context:

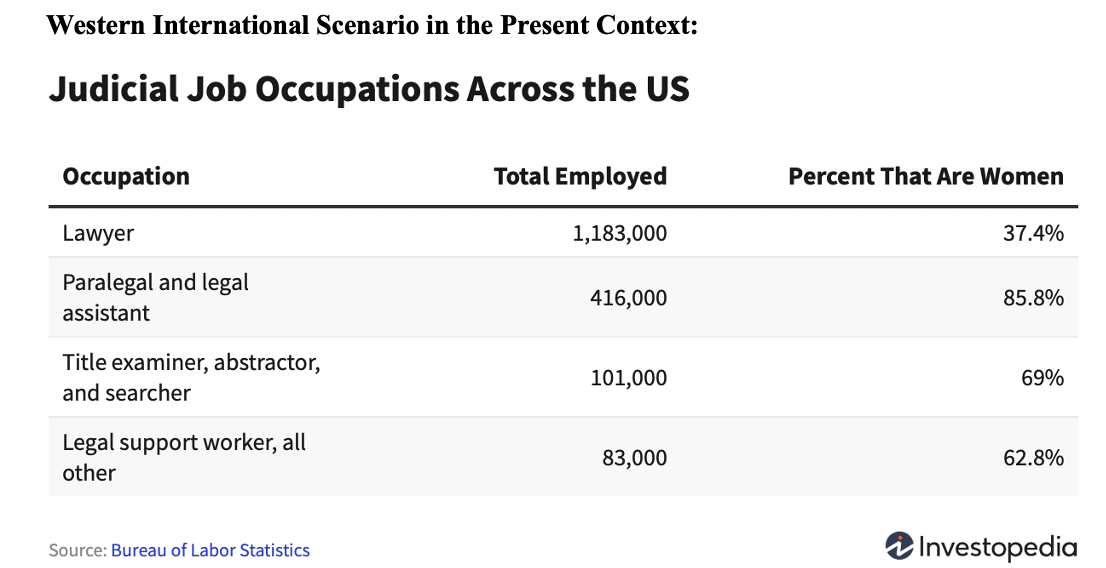

This data also shows that women are more represented in lower level judicial positions such as paralegals, legal assistants, and legal support workers, etc. At the highest level, the Supreme Court, only three of the nine justices are women. The federal court system of the United States is made up of three main levels: district courts (the general trial courts), circuit courts (the court of appeals), and the Supreme Court (the highest court level in the judicial system). It's important to examine all levels of the federal court system because each system has different levels of authority and deals with different kinds of cases.

The district court system is where the general trial courts occur. All federal court cases begin in the district courts, including civil and criminal cases. There are 94 district courts across the country. Of these 94 courts, there are currently 203 women judges, while there are 418 men judges.[3] Women make up about a third of the total number of district court judges. At the district court level, there is one gender nonconforming judge.[4]

In England and Wales, of 106 High Court judges, 22 are women; in the Court of Appeal, eight of 39 judges are female; and in the Supreme Court, of course, Baroness Hale sits alone.[5]

It doesn’t take deep understanding to realise that the presence of women in judiciary across the globe remains abysmal and skewed.

There is a common trend of seeing women in lower judiciary positions but not as many as we go higher up. The reasons could vary from gender stereotyping, inherent bias, social conditioning, and other social factors. However a reinforcement of these social instruments causes a detriment in dispensation of justice.

Some Solutions:

Open conversations, talks and seminars in law schools, workspaces, and judiciary institutions should be conducted in order to acknowledge the unconscious bias, gender and ethnic stereotyping. The identified cause of pipeline leak with insufficient women at senior positions can be improved with realised motivation to better the situation. It is also important to generate discourse and adopt a solution oriented approach to these issues.

Conclusion:

“A lack of pluralism is a denial to users and counsel of the benefit of perspective.”[6]

As wisely as it can be administered, a concentrated group of men alone could almost not suffice for administering justice without taking adequate represented inputs from women judges. It is essential to highlight the impervious effects of such a composition of appointments, promotions and representation, as it cannot entail to the most effective impartial, valued judiciary.

While the visible data and statistics point towards a sub-par weight of women in judiciary, encouragement is required both actively and passively to increase and equate gender representation in judiciary in India and abroad.

[1] http://arbitrationblog.practicallaw.com/will-the-pipeline-leak-be-mended-in-2017/, last visited June 17, 2021.

[2] https://www.investopedia.com/gender-representation-in-the-judiciary-5113183

[3] American Constitution Society. Diversity of the Federal Bench. Accessed Feb. 28, 2021.

[4] Victory Institute. Out for America. Accessed March 4, 2021.

[5] https://www.lag.org.uk/article/201796/-ldquo-the-lack-of-women-in-our-senior-judiciary-remains-a-source-of-embarrassment-and-frustration--rdquo-

[6] Joseph Mamounas, Does “Male, Pale, and Stale” Threaten the Legitimacy of International Arbitration? Perhaps, but There’s No Clear Path to Change, Kluwer Arbitration Blog.

Discourse Resources:

Think India Debating Forum in collaboration with Lawbeat and Sahasi Mission present “RISING TO THE BENCH”: a group discussion on appointment of women in the higher judiciary.

Moving forward with the theme "Rising to the bench", we are glad to introduce a project which will take place in four phases which aims at change-making with; Discourse, Data, Discussion and Direction.

I. Discourse: The first phase is centred around a Group Discussion, the primary goal of which is to generate discourse on the issue of lack of diversity in the higher judiciary.

II. Data: The second phase will be centred around collating empirical data in order to ascertain the cause(s) for this lack of diversity.

III. Discussion: In the third phase, we intend to hold a panel discussion in order to delve into the the issues and challenges faced by female legal luminaries in the legal profession.

IV: Direction: The fourth phase will culminate into formulating recommendations & suggestions that could pave the direction for Diversity.

Date:18-19 July 2021

Registration link: https://bit.ly/35VhMwP

Awards and Recognitions

1) Cash prizes worth Rs.5000/-

2) Participation & Merit Certificates

3) Winners will also get an exclusive chance to interact with legal luminaries during the subsequent panel discussion.

In case of any queries, please feel free to contact: 85911-00039/ 82092-79990.