Ancient Dharma and Modern Power: Rethinking Sovereignty Through India’s Experience

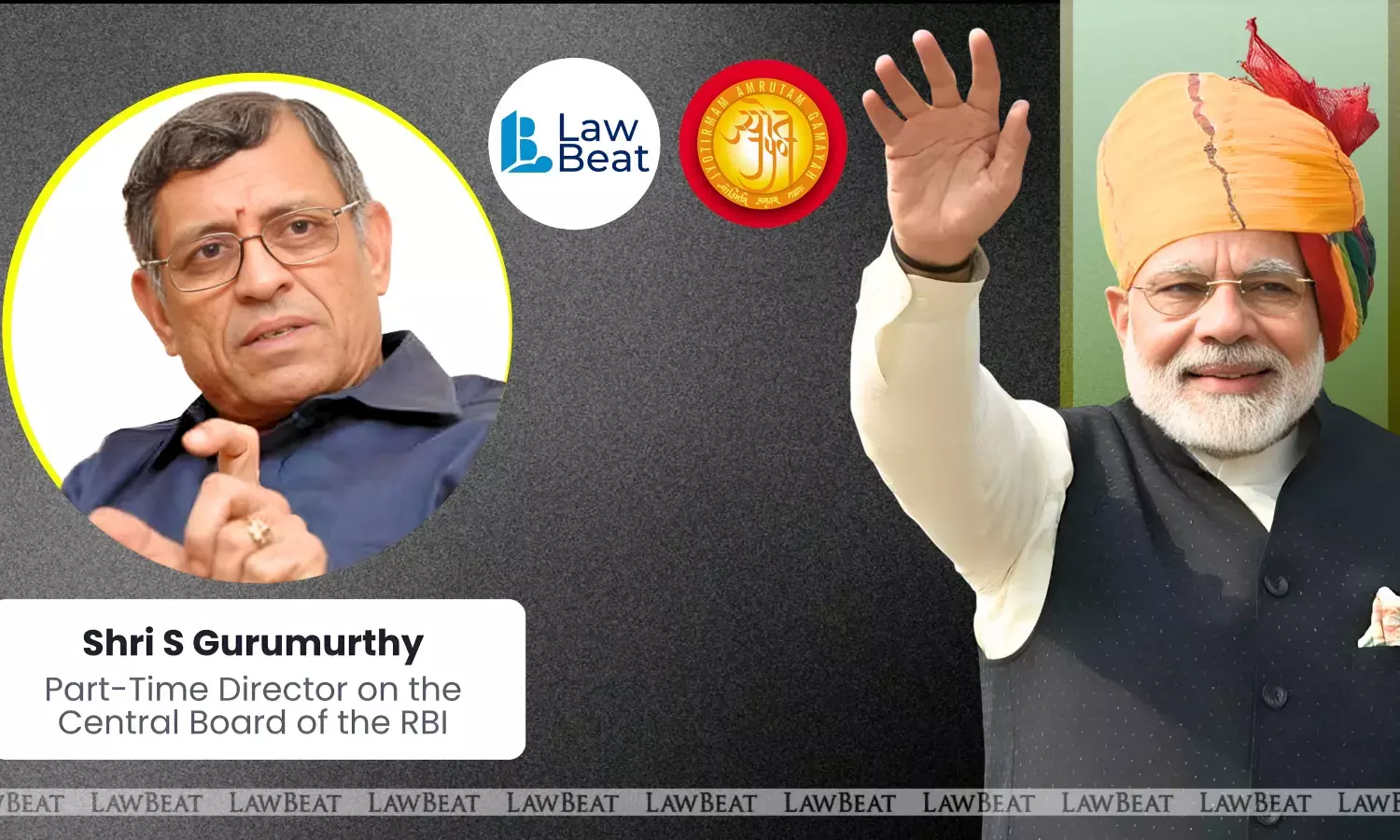

“India Is a Functioning Wonder”: S Gurumurthy on Power, Dharma and the Global Shift

At the Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam Ki Oar 4.0 conclave, S Gurumurthy delivered a sweeping civilisational critique of modern sovereignty, contrasting India’s ancient, Dharma-based understanding of statehood with the Western power-centric model.

Drawing on history, economics, laws of war, ecological ethics and education, he argued that India today stands at a moment of transition caught between tradition and modernity and must rediscover spiritual clarity to meaningfully guide its youth and its global role.

Speaking on India’s place in the world, Gurumurthy described the country as a “functioning wonder.”

Despite occupying only 2.4% of the world’s land area, India supports nearly 18% of the global human population, over 30% of the world’s bovine population, close to 42% of global cattle, and about 8% of the world’s bio-resources. These figures, he argued, challenge the idea that India is a small or fragile geography and instead point to a distinct civilisational model that has enabled coexistence, continuity and survival at an unparalleled scale.

Contrasting ancient Indian and Western notions of sovereignty, Gurumurthy argued that Indian statehood was historically rooted in Dharma, moral restraint, duty and non-violence, whereas Western sovereignty evolved around power and violence. He pointed out that until the Hague Conference of 1899, Western international norms did not clearly distinguish between combatants and non-combatants.

In contrast, he said, Indian traditions had long imposed ethical limits on warfare, exemplified by the principle that a warrior on horseback must not strike an unarmed man on the ground. This, he argued, reflected a civilisational commitment to humane conduct even in conflict.

Turning to global economic narratives, Gurumurthy challenged the long-held belief that India was culturally rich but economically weak. He recalled that Asia once accounted for nearly 66% of the world’s GDP, with India and China together contributing around 60%.

The disruption, he argued, came not from civilisational inadequacy but from colonial intervention. Referring to remarks made by a former Prime Minister describing British rule as the single biggest turning point in India’s development, Gurumurthy suggested that contemporary global shifts indicate a reversal of that historical imbalance, with the West in relative decline and Asia once again on the rise.

Linking sovereignty to ecological ethics, Gurumurthy invoked the idea of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam to explain India’s approach to human–animal coexistence. He noted that meat consumption per hectare today stands at around 3.1 kg and that per capita meat consumption has declined from approximately 5.1 kg per annum in 2001.

According to him, this reflects not scarcity but conscious accommodation, underscoring an indigenous model of sustainability that predates modern environmental regulation.

In closing, Gurumurthy reflected on India’s unresolved tension between tradition and modernity, citing Jawaharlal Nehru’s foreword to सांस्कृति के चार अध्याय by Ramdhari Singh Dinkar. Nehru’s warning, he recalled, was that India had neither fully rejected its traditions nor fully accepted modernity, leaving the nation in a state of confusion.

Gurumurthy argued that this confusion has deepened in contemporary education systems, which, in his view, risk dehumanising individuals and disorienting young minds. He described this as a profound civilisational challenge, one that cannot be addressed through policy or law alone but requires spiritual guidance and clarity.

Through his address, Gurumurthy framed sovereignty not merely as a constitutional or geopolitical concept but as a living civilisational principle shaped by ethics, restraint and self-understanding. As India’s global position evolves amid shifting power structures, he suggested that the country’s greatest task lies in reconciling ancient wisdom with modern realities, without losing either in the process.

The week-long immersive conclave “Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam Ki Oar 4.0 - Sankraman Kaal” organised by JYOT commenced with an opening ceremony that brought together members of the judiciary, the Bar and spiritual leadership to reflect on the convergence of ancient Indian wisdom and contemporary constitutional thought.

At its core, the conference attempts to bridge ancient Indian value systems with contemporary constitutional and legal frameworks. Drawing from ideas rooted in Indian Rajneeti, philosophy, jurisprudence, and civilisational ethics, the conclave explores whether India’s modern legal system is sufficiently equipped, both structurally and institutionally, to integrate indigenous constitutional thought while responding to present-day legal, political and governance challenges.