Electronic Service Of Summons Legally Valid Under BNSS: Bombay HC Sets Aside POCSO Court’s Contrary View

Trial Courts Must Accept Digital Service Of Summons Under BNSS, says Bombay High Court

The Bombay High Court has clarified that summons served through electronic means, including mobile communication, are legally valid under the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, and that criminal courts must align their procedure with the digital framework introduced by the new law.

Holding that the object of a summons is to ensure that a witness receives notice of the proceedings and not to insist on any particular mode of service, the Court ruled that once such knowledge is communicated through a legally recognised electronic method, the service cannot be treated as defective.

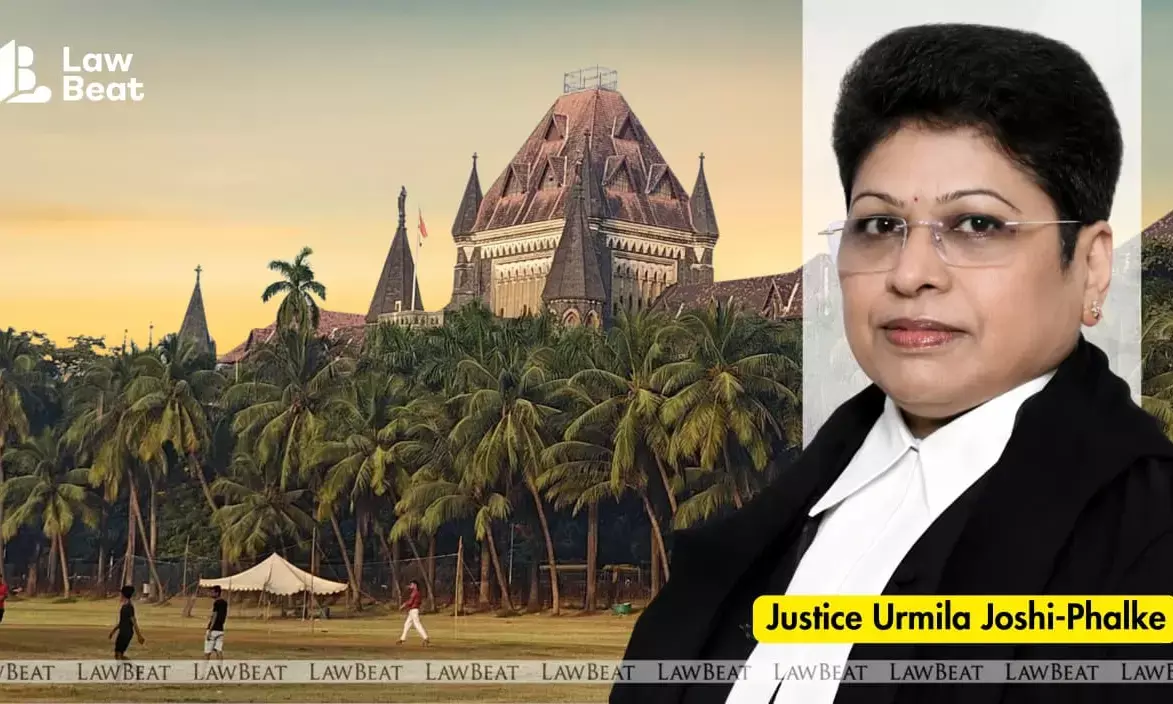

A Single Judge bench of Justice Urmila Joshi-Phalke allowed a criminal application filed by the State and quashed an order of a Special POCSO Court at Nagpur which had imposed costs on a police constable after concluding that service of summons through mobile phone was impermissible.

The High Court held that the trial court had ignored Sections 70 and 530 of the BNSS, which expressly recognise electronic service of summons and permit criminal proceedings to be conducted in electronic mode.

The issue arose in a pending POCSO trial where the matter had been listed for recording prosecution evidence. The Special Court found that certain witnesses were absent and noted from the summons report that service had been effected through mobile phone.

Taking the view that such service was not a valid legal mode, it treated the summons as unserved and imposed costs on the concerned constable for delaying the trial.

Before the High Court, the prosecution contended that this approach was contrary to the statutory scheme introduced by the BNSS.

It was pointed out that the witnesses had earlier been served and had been bound over, and that the subsequent mobile communication was only to inform them of the next date of hearing. It was further submitted that the reissued summons had not even been handed over to the constable for service, a fact reflected in the service record.

Examining the legal position, the High Court referred to Section 70(3) of the BNSS, which provides that summons served through electronic communication shall be deemed to be duly served and that an attested copy of such electronic summons is sufficient proof of service.

The Court also relied on Section 530, which enables all stages of criminal proceedings, including issuance and service of summons, recording of evidence and appellate proceedings, to be conducted through electronic means.

In light of these provisions, the Court held that the legislative intent is to formally incorporate electronic modes into criminal procedure and that courts cannot insist on traditional methods of service in disregard of the amended law.

The Court reiterated that the purpose of service of summons is to bring the proceedings to the notice of the person concerned and to provide a copy of the relevant papers, and that the mode through which such notice is conveyed is secondary once the statute recognises electronic communication.

Applying this principle to the facts of the case, the Court noted that the witnesses had already been served earlier and were aware of the proceedings. The communication through mobile phone was only to inform them of the date, which fulfilled the requirement of notice.

In such circumstances, treating the service as invalid was contrary to the legal position under the BNSS.

The High Court also found the trial court’s factual conclusion to be erroneous, observing that the record showed that after the witnesses were bound over, the fresh summons were not handed to the constable for service.

Imposing costs on the officer for non-service in these circumstances was therefore unjustified.

Holding that the impugned order was unsustainable both in law and on facts, the Court quashed the direction to recover costs from the police constable and disposed of the application.

The ruling assumes significance in the context of the transition to the new criminal procedure regime, where Parliament has expressly provided for digital processes in investigation and trial. It underscores that electronic service of summons is not merely a temporary or pandemic-era arrangement but a statutorily recognised mode, and that trial courts are required to adapt their practice accordingly.

The decision is likely to have a wider bearing on how courts across the country deal with service of summons, witness management and delays in criminal trials in the post-BNSS framework.

Case Title: State of Maharashtra v. Satish

Bench: Justice Urmila Joshi-Phalke

Date: 12.02.2026