AERA's appeal against TDSAT's order maintainable: SC

AERA can file an appeal under Section 31 in view of our conclusion that it is a necessary party in the appeals against the tariff orders issued by it, the bench said

The Supreme Court recently held appeals filed by Airport Economic Regulatory Authority (AERA) of India against orders of Telecom Disputes Settlement and Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) under Section 31 of the AERA Act maintainable.

The apex court rejected a contention by Delhi International Airport Ltd and others that the AERA, being a quasi-judicial body, cannot file an appeal against the judgment of TDSAT.

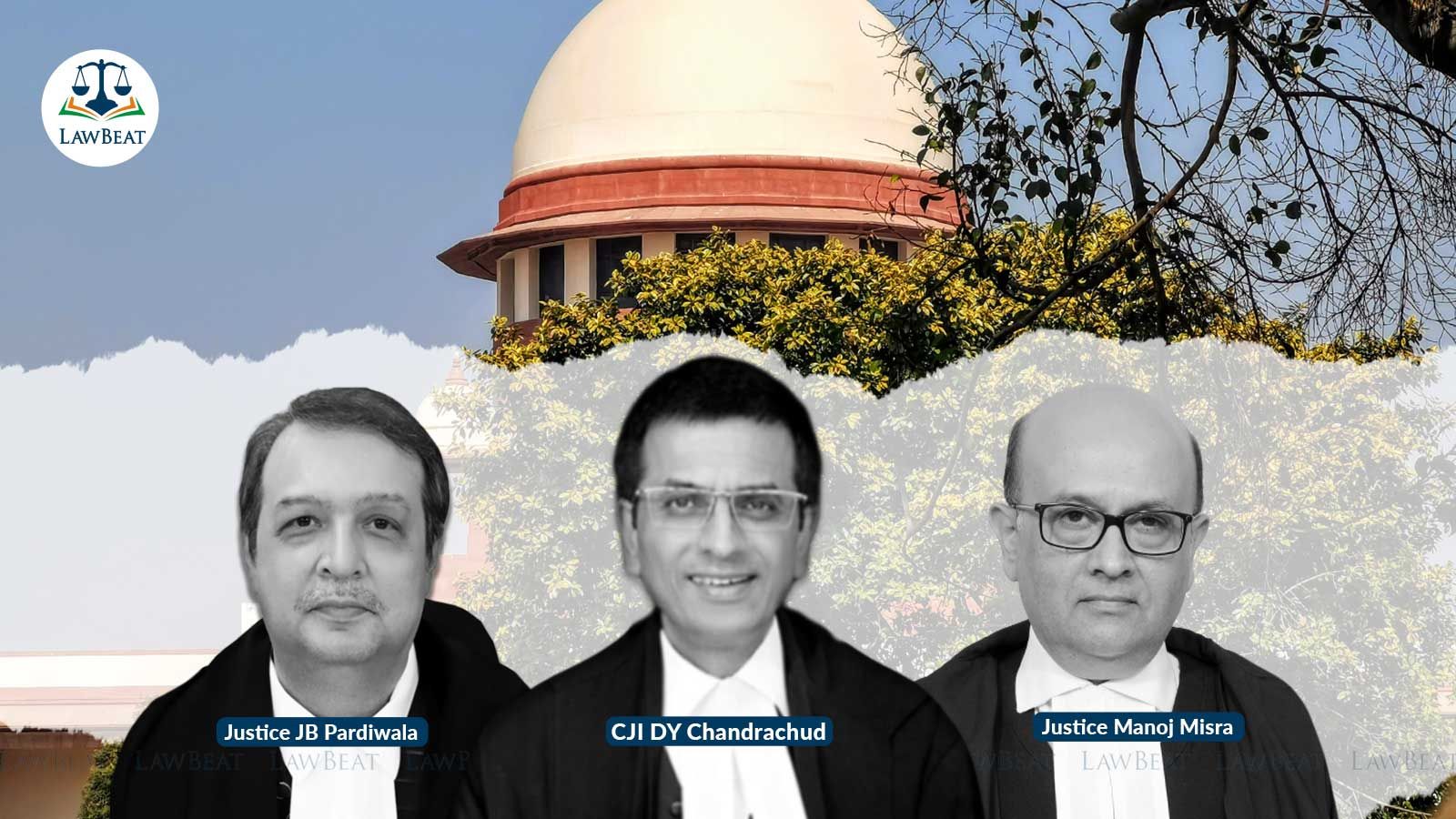

"AERA can file an appeal under Section 31 in view of our conclusion that it is a necessary party in the appeals against the tariff orders issued by it," a bench of Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud and Justices J B Pardiwala and Manoj Misra said.

The TDSAT had in January, 2023 held that AERA cannot regulate tariffs for non-aeronautical services such as cargo and ground handling at major airports, including Delhi and Mumbai.

Dealing with AERA's appeal, the court highlighted the principles that an authority (either a judicial or quasi-judicial authority) must not be impleaded in an appeal against its order if the order was issued solely in exercise of its “adjudicatory function”.

However, "An authority must be impleaded as a respondent in the appeal against its order if it was issued in exercise of its regulatory role since the authority would have a vital interest in ensuring the protection of public interest; and an authority may be impleaded as a respondent in the appeal against its order where its presence is necessary for the effective adjudication of the appeal in view of its domain expertise," the bench said.

The respondents contended that AERA which is a tariff fixing authority, cannot be an “aggrieved party” at any stage of the proceedings. Since it cannot file an appeal before TDSAT, it also cannot file an appeal before this Court under Section 31 of the Act assailing the order of TDSAT, they said.

The Union government said AERA is concerned with the outcome of the decision by TDSAT on, inter alia, ‘tariff determination’ in its own interest as a regulatory body and in the interest of the general public. They also said, AERA will always be a contesting respondent when an appeal against its order or direction is filed before TDSAT.

They also said AERA is not a quasi-judicial authority. It is a regulator which performs multiple functions other than determination of tariff.

Even assuming that AERA is a quasi-judicial authority, the embargo that applies to judicial authorities, that they cannot contest an appeal against their own orders, need not always apply to quasi-judicial authorities, they contended.

The court said a judicial or a quasi-judicial authority may be required to be impleaded as a party in a challenge against its order if it is necessary as in case of a writ of certiorari.

Second, this court has consistently drawn a distinction between courts in the “strictest sense” and Tribunals because the former are nearly never involved in a ‘lis’ and perform a purely adjudicatory function, the bench pointed out.

"However, a statutory authority may be entrusted with the performance of both adjudicatory and regulatory functions. This court has held that while it need not be impleaded as a respondent in an appeal against an adjudicatory order, it may be made a contesting party in an appeal against an order issued in exercise of its regulatory functions because then it may have a vital interest in the ‘lis’ bearing on matters of public interest," the bench said.

The court also pointed out the Competition Act, unlike the AERA Act, expressly provides the statutory authority with the right to present its case before the Appellate Tribunal.

The bench pointed out that the term “quasi-judicial” came into vogue to describe the exercise of power which though administrative in some respects was required to be exercised judicially, that is, in accordance with the principles of natural justice because of its impact on the rights of persons affected.

It said the exercise of power by Authorities and Tribunals was described as “quasi-judicial’ to ensure that the principles of natural justice were complied with. However, with the evolution of the doctrine of fairness and reasonableness, all administrative actions (even if there is nothing ‘judicial (or adjudicatory)’ about them) are required to comply with the principles of natural justice.

The evolution of the fairness doctrine has transcended many boundaries. Thus, the reason for which the expression ‘quasi-judicial’ came into vogue is no longer relevant. Neither are the tests to identify them because the functions of an authority no more need to have any semblance to ‘judicial functions’ for it to act judicially (that is, comply with the principles of natural justice), the bench said.

The court, on an analysis of the statutory provisions, said it can be reasonably concluded that AERA is performing a regulatory function while determining tariff under Section 13(1)(a) of the AERA Act.

"Modern constitutional governance requires that legislation is not general but context specific. Over-emphasising the distinction between general and specific provisions to determine if a function is regulatory or adjudicatory would be to completely ignore the jurisprudential developments governing both the regulatory domain and Article 14," the bench said.

The court also said when it comes to appeals against the tariff orders issued by AERA, it is not just acting as an ‘expert body’ but as a regulator interested in the outcome of the proceedings.

AERA has a statutory duty to regulate tariff upon a consideration of multiple factors to ensure that airports are run in an economically viable manner without compromising on the interests of the public. This statutory role is evident, inter alia, from the factors that AERA must consider while determining tariff and the power to amend tariff from time to time in public interest, the court said.

When AERA determines the tariff for aeronautical services in terms of Section 13(1)(a) of the AERA Act, it is acting as a regulator and an interested party. It is interested not in a personal capacity. Its interest lies in ensuring that the concerns of public interest which animate the statute and the performance of its functions by AERA are duly preserved. Thus, AERA is a necessary party in the appeal against its tariff order before TDSAT and it must be impleaded as a respondent.

Section 18(5) refers to parties in a dispute or appeal. AERA is not a party to the lis when TDSAT adjudicates a dispute between two or more service providers, or a service provider and a consumer in terms of Section 17(1)(a). For disputes adjudicated by TDSAT under Section 17(a), AERA may be included as a party in terms of the proviso to the provision. If the expression “as the case may be” is interpreted to refer to “dispute or appeal”, thereby excluding AERA as a party to either the dispute or the appeal, it would amount to reading down the proviso to Section 17(1)(a), the bench said.

The court, while holding the maintainability of appeals, directed its registry to list the matter before regular bench for adjudication of the appeals on merits.

Case Title: Airport Economic Regulatory Authority of India Vs Delhi International Airport Ltd & Ors