Can Police Take Back Someone Released On Bail? Supreme Court Answers

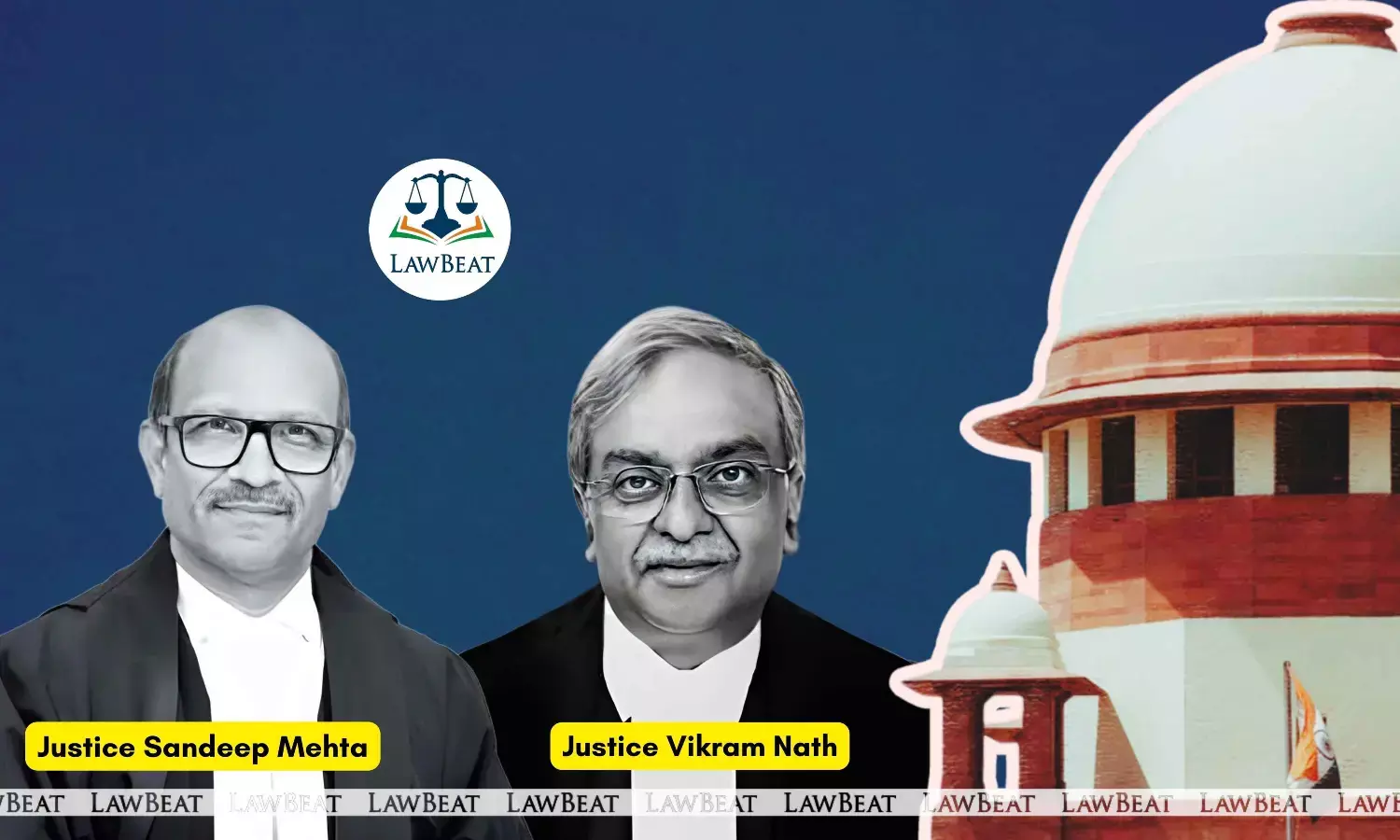

Supreme Court of India Judges, Justices Vikram Nath & Sandeep Mehta

The Supreme Court has ruled that when an accused is released on bail, police custody cannot be granted as long as the bail order remains in force.

The bench stated that where the investigating agency seeks police remand of an accused who has already been released on bail, the proper and legally permissible course is to first seek cancellation of bail in accordance with law and only thereafter apply for police custody.

The scheme of criminal procedure does not allow grant of police remand of an accused who continues to enjoy the protection of bail, as such a course would effectively defeat and nullify the order granting bail.

The ruling came in a criminal appeal filed by Pogadadabnda Revathi and another against the Telangana High Court's order of October 13, 2025.

Appellants Revathi and Bandi Sandhya were arrested in connection with an FIR and were presented before the Additional Chief Judicial Magistrate, Hyderabad on March 12, 2025. They were remanded to judicial custody till March 26, 2025.

On March 13, 2025, the Inspector of Police, Cyber Crimes Police Station, Hyderabad moved an application seeking police custody of the accused appellants for five days. The application was rejected on March 17, 2025.

By a separate order on the same date, March 17, 2025, the magistrate released the accused appellants on bail.

Allowing a revision application, the Sessions Judge at Nampally, Hyderabad on September 26, 2025 directed that the accused appellants would be remanded to police custody from October 6, 2025 to October 8, 2025. However, the order was subsequently modified, altering the period of custody from October 13, 2025 to October 15, 2025.

The Supreme Court noted that in the order granting police custody of the accused appellants, the Sessions Judge completely overlooked the fact that they had already been granted regular bail by the magistrate on March 17, 2025.

The accused appellants approached the High Court, which dismissed their plea on October 13, 2025.

The appellants' counsel argued that neither the Sessions Court nor the High Court applied mind to the fact that police custody remand had been denied by the magistrate with cogent reasons and the accused appellants had also been released on bail.

Directing police custody of the accused appellants nearly seven months after they had been released on bail without due appreciation of the reasons assigned in the magistrate's order is abuse of the process of law. As long as the order granting bail remains in force, no direction granting police custody could have been lawfully issued.

The Supreme Court noted the High Court relied on provisions of Section 187 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, corresponding to Section 167 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973. This provision states that police custody for a term not exceeding 15 days in whole or in parts may be granted by the magistrate during the initial 40 days or 60 days out of total detention period.

Since none of the offences were punishable with death, imprisonment for life or imprisonment for a term of 10 years or more, the statutory period applicable for grant of police custody would be 40 days.

The bench emphasized that discretion whether or not to grant police custody remand is vested exclusively with the magistrate. Once the magistrate exercises such discretion accepting or declining the prayer for police custody by assigning reasons, such order should ordinarily not be interfered with by the revisional forum unless gross perversity is shown.

The court found the Sessions Judge, while accepting the revision, completely overlooked the magistrate's order and recorded that further recoveries were to be made from the accused appellants and their detailed confessional statements had to be recorded, making police custody essential.

The court found both reasons unacceptable and perverse on the face of record. The magistrate's order specifically referred to recoveries of subject devices used for posting offensive messages having been effected and extensive interrogation having been carried out from the accused appellants.

The Sessions Judge, while exercising revisional jurisdiction, ought not to have interfered in the well-reasoned order passed by the magistrate. The Sessions Judge did not even consider the magistrate's order in the correct perspective while deciding the revision.

The court pointed out the order granting police custody was passed by the revisional court after more than six months from the date on which police custody was declined by the magistrate and the accused appellants were released on bail.

When the accused appellants had already been released on bail, granting police custody for three days would necessarily require them to be taken back into custody and curtailing their liberty. This would, in effect, amount to cancellation of bail in an indirect manner without adherence to settled legal parameters governing bail cancellation.

Citing Satyajit Ballubhai Desai vs State of Gujarat (2014), the bench pointed out the principle makes it clear that when an accused is released on bail, police custody cannot be granted as long as the bail order continues to operate.

The court held the accused appellants stood released on bail by effect of the order of March 27, 2025 passed by the magistrate, which has not been challenged before any forum. Consequently, grant of police custody in face of an existing bail order would amount to indirect cancellation of bail.

The court allowed the appeal and set aside the orders passed by the Sessions Court and the High Court.

Case details: Pogadadabnda Revathi & Anr vs The State of Telangana, decided by a bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Sandeep Mehta on January 9, 2026.