'Can't Reject Child Witness Testimony Outrightly': SC Reverses Man’s Acquittal in Wife’s Murder

The Supreme Court said courts are expected to deal with such cases more realistically and not discard evidence on account of procedural technicalities, perfunctory considerations, or insignificant lacunas

The Supreme Court recently noted that the Evidence Act does not prescribe any minimum age for a witness, affirming that a child witness is a competent witness and his or her evidence cannot be rejected outrightly.

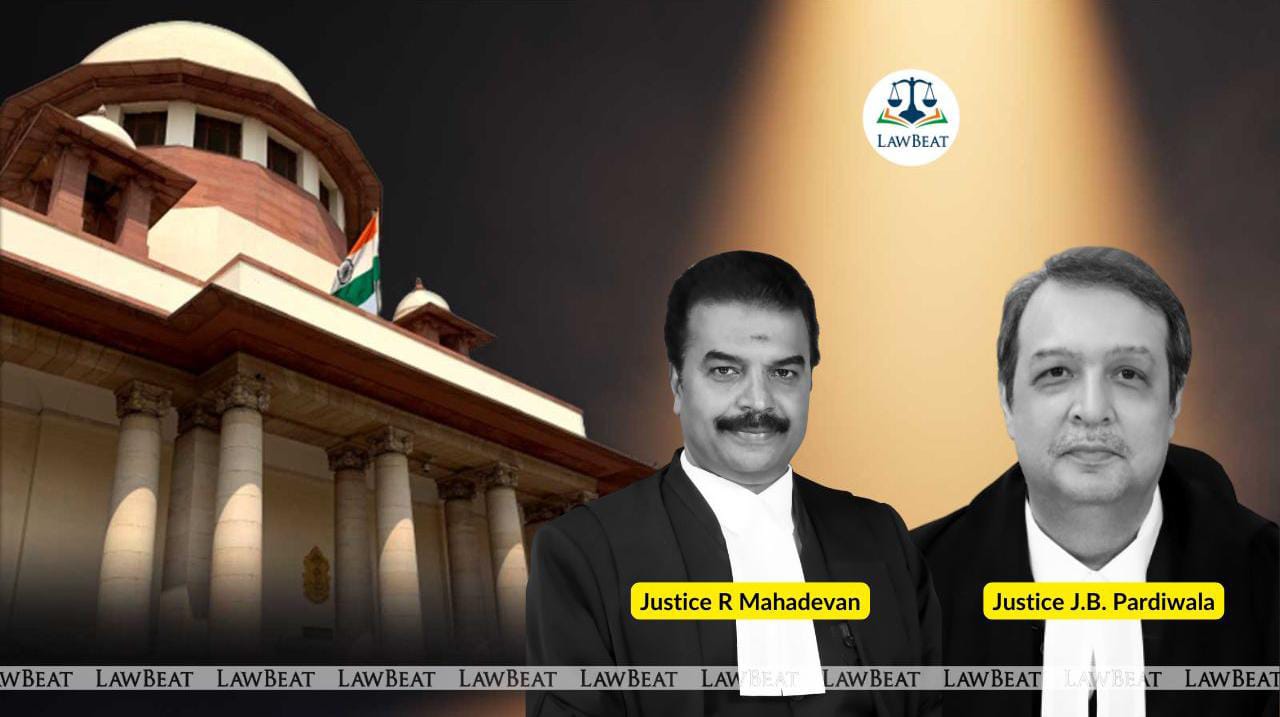

The bench of Justices J B Pardiwala and R Mahadevan allowed an appeal filed by the Madhya Pradesh government against the high court's decision to reverse the conviction and sentence of life term imposed by the trial court upon respondent Balveer Singh for killing his wife on July 15, 2003.

The seven-year-old child witness, the appellant's daughter, had deposed that her mother (the deceased), her two infant brothers, and her aunt were present in the house. At that time, her father (the respondent-accused) came and grabbed her mother from her neck and hit a blow on her body with a stick causing her to fall. Thereafter, her father exerted pressure on mother's neck with his feet, and as a result, she screamed for help. When the daughter ran to help her mother, the father slapped her and her aunt pulled her away. The child deposed that she did not witness what happened next but later she saw her mother dead and her body being taken by her father to the barn. She further deposed that early in the morning she found the body of her mother burning.

The trial court had held the father guilty of murder and destruction of evidence, finding the child witness as trustworthy and reliable. It had also noted her evidence was corroborated by other materials on record.

Upon appeal, the high court had acquitted the father, holding the child witness' testimony appeared to be very shaky not inspiring confidence, more particularly, in view of the inordinate delay of 18 days in recording her police statement under Section 161 CrPC. It had also noted the child had been residing after the incident with her maternal uncle and could have been tutored due to the fact that they were on inimical terms with the accused father.

In its analysis, the apex court pointed out the Evidence Act does not prescribe any particular age as a determinative factor to treat a witness to be a competent one.

"On the contrary, Section 118 of the Evidence Act envisages that all persons shall be competent to testify, unless the court considers that they are prevented from understanding the questions put to them or from giving rational answers to these questions, because of tender years, extreme old age, disease - whether of mind, or any other cause of the same kind. A child of tender age can be allowed to testify if he has intellectual capacity to understand questions and give rational answers thereto," the bench said.

Relying upon previous judgments, the bench said that the evidence of a child witness for all purposes is deemed to be on the same footing as any other witness as long the child is found to be competent to testify.

"The only precaution which the court should take while assessing the evidence of a child witness is that such witness must be a reliable one due to the susceptibility of children by their falling prey to tutoring. However, this in no manner means that the evidence of a child must be rejected outrightly at the slightest of discrepancy, rather what is required is that the same is evaluated with great circumspection," the bench said.

While appreciating the testimony of a child witness, the bench said, the courts are required to assess whether the evidence of such a witness is its voluntary expression and not borne out of the influence of others and whether the testimony inspires confidence.

"At the same time, one must be mindful that there is no rule requiring corroboration to the testimony of a child witness before any reliance is placed on it. The insistence of corroboration is only a measure of caution and prudence that the courts may exercise if deemed necessary in the peculiar facts and circumstances of the case," the court said.

In the present case, the bench pointed out that no question whatsoever was put to the Investigating Officer to explain the reason for the delay in examination of the child witness.

"We should not willingly jump to discard her testimony on the ground of delay alone, and ought to be circumspect while scrutinising the effect of such delay. The court in such a situation would be required to carefully see whether there is anything palpable on the face of it to indicate any malice at the end of the investigating agency in belatedly examining such witness," the bench said.

It found nothing on record that would lead to the inference that the delay in recording her statement was done deliberately in order to manipulate or concoct the case against the accused father, and rather such delay appeared to be inadvertent with no sinister motive or design in mind.

It attributed the delay to "overall investigation inertia and not to give effect to any unfair practice" as another witness statement was recorded on the same day.

The Supreme Court said the high court appeared to have lost sight of the fact that the child witness at the relevant point of time was only seven years of age. She had not only lost her mother but had also been abandoned by her father who went absconding. In such circumstances, the only option available to her was to reside with her maternal uncle.

"Where else does the High Court expect a child of such tender age in such circumstances to reside? How could the High Court even possibly expect such child to go to the police station unaccompanied by any adult family member to give her statement," the court asked.

The apex court held that her testimony could not have been discarded solely on the ground that it was recorded in the presence of her maternal uncle, an interested witness, who was on inimical terms with the accused father.

"The courts are expected to deal with such cases in a more realistic manner and not discard evidence on account of procedural technicalities, perfunctory considerations or insignificant lacunas," the bench said.

It stressed that the appreciation of the testimony of a witness is a hard task and there is no fixed or straight jacket formula for appreciation of the ocular evidence.

The bench summarised its conclusion:

(I) The Evidence Act does not prescribe any minimum age for a witness, and as such a child witness is a competent witness and his or her evidence and cannot be rejected outrightly.

(II) As per Section 118 of the Evidence Act, before the evidence of the child witness is recorded, a preliminary examination must be conducted by the Trial Court to ascertain if the child-witness is capable of understanding sanctity of giving evidence and the import of the questions that are being put to him.

(III) Before the evidence of the child witness is recorded, the Trial Court must record its opinion and satisfaction that the child witness understands the duty of speaking the truth and must clearly state why he is of such opinion.

(IV) The questions put to the child in the course of the preliminary examination and the demeanour of the child and their ability to respond to questions coherently and rationally must be recorded by the Trial Court.

(V) The testimony of a child witness who is found to be competent to depose i.e., capable of understanding the questions put to it and able to give coherent and rational answers would be admissible in evidence.

(VI) The Trial Court must also record the demeanour of the child witness during the course of its deposition and cross-examination and whether the evidence of such child witness is his voluntary expression and not borne out of the influence of others.

(VII) There is no requirement or condition that the evidence of a child witness must be corroborated before it can be considered. A child witness who exhibits the demeanour of any other competent witness and whose evidence inspires confidence can be relied upon without any need for corroboration and can form the sole basis for conviction.

(VIII) Corroboration of the evidence of the child witness may be insisted upon by the courts as measure of caution and prudence where the evidence of the child is found to be either tutored or riddled with material discrepancies or contradictions.

(IX) Child witnesses are considered as dangerous witnesses as they are pliable and liable to be influenced easily, shaped and moulded and as such the courts must rule out the possibility of tutoring.

(X) The evidence of a child witness is considered tutored if their testimony is shaped or influenced at the instance of someone else or is otherwise fabricated.

(XI) Merely because a child witness is found to be repeating certain parts of what somebody asked her to say is no reason to discard her testimony as tutored.

(XII) Part of the statement of a child witness, even if tutored, can be relied upon, if the tutored part can be separated from the untutored part, in case such remaining untutored or untainted part inspires confidence.

The apex court held that the high court had committed an egregious error in discarding the testimony of the child witness, noting that she was examined at length for 1.5 hours and there was nothing to indicate she had been tutored or was deposing falsely. In the entire cross examination, no significant contradictions were found, it pointed out.

Referring to the principles of circumstantial evidence, the bench noted the unnatural conduct of the respondent accused in not informing the family members either about the death of their daughter or the cremation of her body, despite the fact that her family members were residing in the very same village.

The court also found that the high court whilst passing the impugned judgment and order completely failed to advert to and refer to Section 106 of the Evidence Act, which was crucial in a case involving circumstantial evidence of such nature.

Section 106 of the Evidence Act would apply to cases where the prosecution could be said to have succeeded in proving facts from which a reasonable inference can be drawn regarding the guilt of the accused, the court said.

"If an offence takes place inside the four walls of a house and in such circumstances where the accused has all the opportunity to plan and commit the offence at the time and in the circumstances of its choice, it will be extremely difficult for the prosecution to lead direct evidence to establish the guilt of the accused. It is to resolve such a situation that Section 106 of the Evidence Act exists in the statute book," the bench said.

In the case, the court noted the offence took place within four walls, the accused failed to inform family members of the deceased, his running away, and failure to explain the circumstances, which shifted the burden upon him.

The apex court finally set aside the high court's judgment and restored the trial court's decision holding him guilty in the case. It ordered the respondent accused to surrender within four weeks to serve the sentence.

Case Title: The State of Madhya Pradesh Vs Balveer Singh