Negation of Bail the Rule in NDPS Cases with 10+ Year Jail Term: SC

SC stressed any lapse or delay in compliance of Section 52A of the NDPS Act by itself would neither vitiate the trial nor would entitle the accused to be released on bail

The Supreme Court on December 20, 2024, observed that in the NDPS cases, where the offence is punishable with a minimum sentence of ten years, the accused shall generally be not released on bail as negation of bail is the rule and its grant is an exception in such matters.

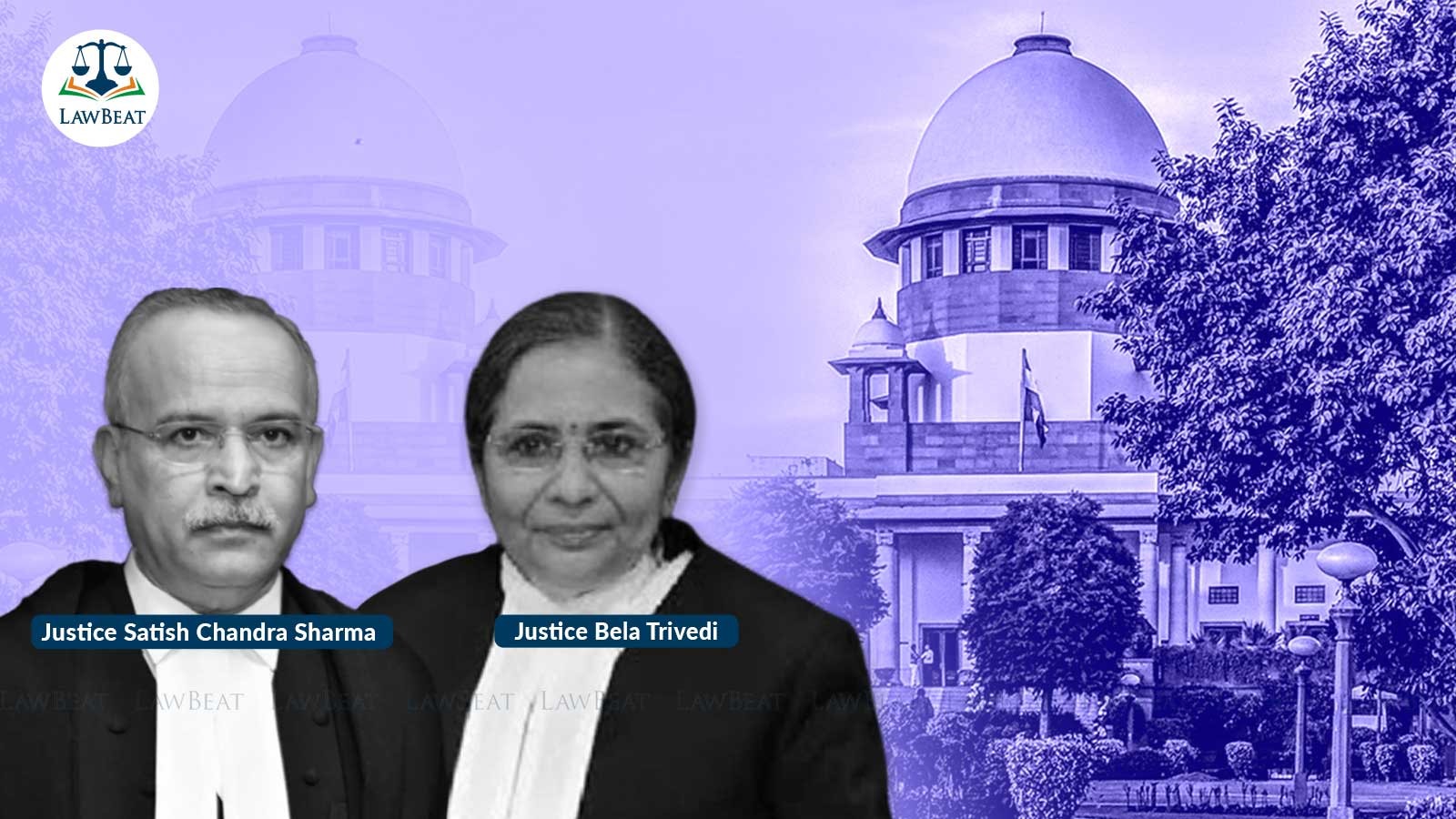

A bench of Justices Bela M Trivedi and Satish Chandra Sharma set aside the Delhi High Court's order of May 18, 2023, granting bail to an accused solely on the ground of belated compliance with Section 52A of the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1985, misinterpreting the provision, and without recording the findings as mandated in Section 37 of the said Act.

The bench emphasised that Section 52A was inserted only for the purpose of early disposal of the seized contraband drugs and substances, considering the hazardous nature, vulnerability to theft, constraint of proper storage space etc.

"There cannot be any two opinions on the issue about the early disposal of the contraband drugs and substances, more particularly when it was inserted to implement the provisions of International Convention on the Narcotics Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, however delayed compliance or non-compliance of the said provision by the concerned officer authorised to make application to the Magistrate could never be treated as an illegality which would entitle the accused to be released on bail or claim acquittal in the trial, when sufficient material is collected by the Investigating Officer to establish that the Search and Seizure of the contraband substance was made in due compliance of the mandatory provisions of the Act," the bench said.

The bench also pointed out that it has been the consistent and persistent view of the top court that while considering the application for bail, the court has to bear in mind the provisions of Section 37 of the NDPS Act, which are mandatory in nature.

"The recording of finding as mandated in Section 37 is a sine qua non for granting bail to the accused involved in the offences under the said Act. Apart from the granting opportunity of hearing to the Public Prosecutor, the other two conditions i.e., (i) the satisfaction of the court that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is not guilty of the alleged offence and that (ii) he is not likely to commit any offence while on bail, are the cumulative and not alternative conditions," the bench said.

In the case, the bench noted that the respondent-accused Kashif filed the bail application directly in the High Court without first approaching the Special Court, and curiously the High Court without considering as to whether the twin conditions mentioned in clause (b) sub-section (1) of Section 37 were fulfilled or not, concluded without any material on record that Section 37 was not attracted as there was non-compliance of Section 52A of the said Act within reasonable time.

"It was obligatory on the part of the High Court to record a satisfaction on the cumulative conditions namely, that there were reasonable grounds for believing that the respondent - accused was not guilty of the alleged offences and that he was not likely to commit any offence while on bail, as contemplated in Section 37(1)(b) of the said Act. The non-recording of such satisfaction which is mandatory in nature, has rendered the impugned order of High Court fallacious and untenable," the bench said.

The bench said that the impugned order, based on the inferences and surmises, in utter disregard of the statutory provision of the Act and utter disregard of the mandate contained in Section 37 of the Act, and granting bail to the accused merely on the ground that the compliance of Section 52A was not done within reasonable time, was highly erroneous.

Since the High Court had not considered the application of the respondent on merits, the top court remanded the matter for a fresh consideration by extending the period of bail for four weeks to decide the matter preferably within the such period. The court also requested the Chief Justice to post the matter before the bench other than the one which passed the impugned order.

In the case, since the High Court had released the respondent-accused on bail solely on the ground that there was non-compliance of Section 52A of the said Act within reasonable time, the top court examined the scope and ambit as also the repercussions of non-compliance or belated compliance of the said provision.

The court pointed out the statutory provision as contained in Section 52A for disposal of seized narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances came to be inserted in the Act with effect from May 29, 1989, by specifically mentioning that it was for giving effect to the International Conventions.

The bench also pointed out the insertion of Section 52A was followed by the Standing Order considered necessary and expedient to determine the manner in which the narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances should be disposed of after their seizure, having regard to their hazardous nature, vulnerability to theft, substitution and constraints of proper storage space.

The court noted Clause 2.1 of the said Standing Order No.1 of 1989 stated that all drugs shall be properly classified, carefully weighed and sampled on the spot of seizure. The said standing order also provided about the drawal of samples on the spot of recovery, quantity to be drawn for sampling, etc. It also provided a detailed procedure with regard to the method of drawal of representative samples, storage of samples, dispatch of samples, preparation of inventory, etc, and also provided for an early disposal of drugs and other articles by having recourse to the provisions of subsection (2) of Section 52A of the Act.

The court pointed out that sub-section (2) of Section 52A specifies the procedure as contemplated in sub-section (1) thereof, for the disposal of the seized contraband or controlled narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances.

"Any deviation or delay in making the application under subsection (2) by the concerned officer to the Magistrate or the delay on the part of the Magistrate in deciding such application could at the most be termed as an irregularity and not an illegality which would nullify or vitiate the entire case of the prosecution," the bench said.

The bench pointed out that jurisprudence as developed by the courts so far, makes a clear distinction between an “irregular proceeding” and an “illegal proceeding.”

"While an irregularity can be remedied, an illegality cannot be. An irregularity may be overlooked or corrected without affecting the outcome, whereas an illegality may lead to nullification of the proceedings. Any breach of procedure of rule or regulation which may indicate a lapse in procedure, may be considered as an irregularity, and would not affect the outcome of legal proceedings but it can not be termed as an illegality leading to the nullification of the proceedings," the bench said.

The court also pointed out that as per Section 54 of the said Act, the courts are entitled to presume, unless and until the contrary is proved that the accused had committed an offence under the Act in respect of any narcotic drug or psychotropic substance etc for the possession of which he failed to account satisfactorily.

"An anomalous situation would arise if a non-compliance or delayed compliance of Section 52A is held to be vitiating the trial or entitling the accused to be released on bail, though he is found to have possessed the contraband substance, and even if the statutory presumption is not rebutted by him. Such could not be the intention of the legislature," the bench said.

Relying upon the Constitution Bench in the case of Pooran Mal Vs Director of Inspection (Investigation) New Delhi and Others and State of Punjab Vs Baldev Singh (1999), the court pointed out that any procedural illegality in conducting the search and seizure by itself, would not make the entire evidence collected thereby inadmissible.

"We have considered the legislative history of Section 52A and other Statutory Standing Orders as also the judicial pronouncements, which clearly lead to an inevitable conclusion that delayed compliance or noncompliance of Section 52A neither vitiates the trial affecting conviction nor can be a sole ground to seek bail. In our opinion, the decisions of Constitution benches in case of Pooran Mal and Baldev Singh must take precedence over any observations made in the judgments made by the benches of lesser strength, which are made without considering the scheme, purport and object of the Act and also without considering the binding precedents," the bench said.

The court also observed that every law is designed to further the ends of justice and not to frustrate it on mere technicalities. If the language of a Statute in its ordinary meaning and grammatical construction leads a manifest contradiction of the apparent purpose of the enactment, a construction may be put upon it which modifies the meaning of the words, or even the structure of the sentence. It is equally settled legal position that where the main object and intention of a statute are clear, it must not be reduced to a nullity by the draftsman’s unskillfulness or ignorance of the law, the top court said.

In its judgment, the bench summarised its findings as:

(I) The provisions of NDPS Act are required to be interpreted keeping in mind the scheme, object and purpose of the Act; as also the impact on the society as a whole. It has to be interpreted literally and not liberally, which may ultimately frustrate the object, purpose and Preamble of the Act.

(ii) While considering the application for bail, the court must bear in mind the provisions of Section 37 of the NDPS Act which are mandatory in nature. Recording of findings as mandated in Section 37 is sine qua non is known for granting bail to the accused involved in the offences under the NDPS Act.

(iii) The purpose of insertion of Section 52A laying down the procedure for disposal of seized Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, was to ensure the early disposal of the seized contraband drugs and substances. It was inserted in 1989 as one of the measures to implement and to give effect to the International Conventions on the Narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances.

(iv) Sub-section (2) of Section 52A lays down the procedure as contemplated in sub-section (1) thereof, and any lapse or delayed compliance thereof would be merely a procedural irregularity which would neither entitle the accused to be released on bail nor would vitiate the trial on that ground alone.

(v) Any procedural irregularity or illegality found to have been committed in conducting the search and seizure during the course of investigation or thereafter, would by itself not make the entire evidence collected during the course of investigation, inadmissible. The court would have to consider all the circumstances and find out whether any serious prejudice has been caused to the accused.

(vi) Any lapse or delay in compliance of Section 52A by itself would neither vitiate the trial nor would entitle the accused to be released on bail. The court will have to consider other circumstances and the other primary evidence collected during the course of investigation, as also the statutory presumption permissible under Section 54 of the NDPS Act.

Case Title: Narcotics Control Bureau Vs Kashif