Prior Sanction Mandatory for Prosecuting Public Servants Acting in Official Capacity: SC

Court held the high court erred in not considering the fact that the sanction for prosecution was not granted by the competent authority under Section 197 of the CrPC and eventually the sanction was expressly denied by the competent authority with respect to the allegations against the appellant

The Supreme Court on February 25, 2025, said that if a public servant was acting in the performance of their official duties, prior sanction for their prosecution is a condition precedent to the court's cognizance of the case against them.

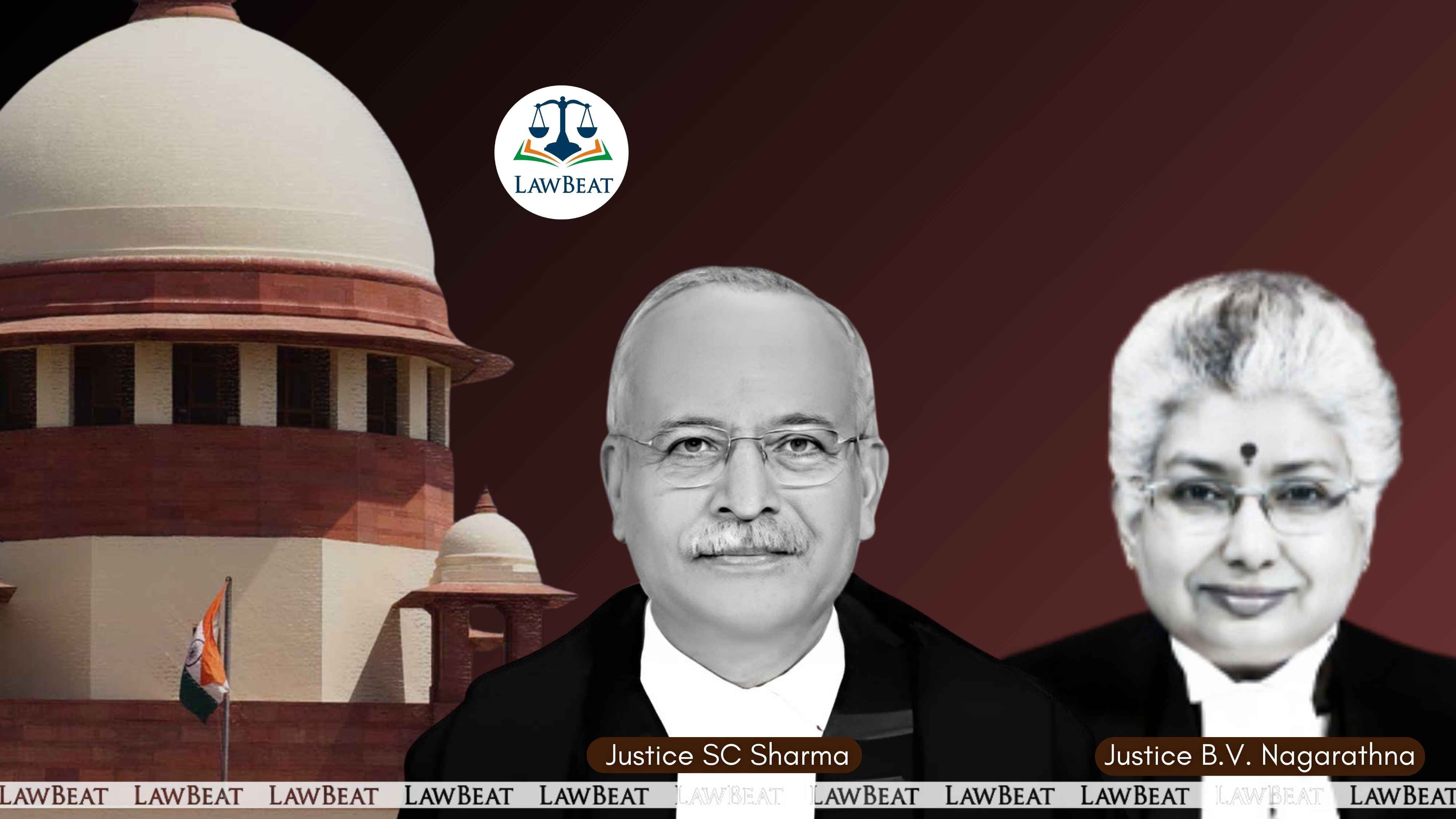

A bench of Justices B.V. Nagarathna and Satish Chandra Sharma ruled that the criminal proceedings against Suneeti Toteja, a Bureau of Indian Standards employee and former FSSAI director, were vitiated due to the absence of prior sanction. The court rejected the argument of deemed sanction, citing judgments in the Vineet Narain and Subramanian Swamy cases.

The appellant, as the presiding officer of the Internal Complaints Committee, was accused of threatening and pressuring a complainant to withdraw her sexual harassment complaint and representing her before the Central Administrative Tribunal without authorization.

The appellant was initially not named in the FIR, but based upon the complainant's statement recorded under Section 164 of the Criminal Procedure Code, a charge sheet was filed against her. Upon the magistrate taking cognizance of the charge sheet, the appellant approached the high court, which dismissed her plea for quashing the proceedings.

The appellant's counsel submitted that she was a government servant who had acted in the course of her official duties, and therefore, cognizance could not have been taken against the offences alleged against her in the absence of a valid sanction for prosecution granted by the concerned authority. She pointed out that the BIS had categorically denied the sanction for the prosecution of the appellant on November 14, 2022.

Uttar Pradesh government's counsel cited Vineet Narain Vs Union of India, to contend that the time limit of three months for grant of sanction for prosecution had to be strictly adhered to and therefore, in light of the fact that no sanction was granted by the competent authority within the stipulated time period, the State was correct in proceeding on the basis of deemed sanction. It submitted that enough material was available on record to proceed against the appellant, and once the cognizance had been taken and the trial had commenced, it was not open for the proceedings to be quashed on the ground of refusal of sanction for prosecution.

The complainant's counsel submitted that the appellant and the other co-accused had filed applications before the trial court for seeking discharge in the matter. It was contended the appellant had annexed only the summoning order to give an impression that the trial court had mechanically issued summons to the accused and not applied its mind, but in fact the trial court had also filed a separate detailed order. The accused had also filed a discharge plea.

The complainant's counsel cited Subramanian Swamy Vs Manmohan Singh, (2012) to contend that if no decision is taken by the sanctioning authority, then at the end of the extended time limit, sanction will be deemed to have been granted to the proposal for prosecution.

Examining the facts of the matter, the bench said the allegations of sexual harassment levelled by the complainant dated back to the year 2012. The enquiry under the provisions of the POSH Act took place during the year 2014-15, and the final enquiry report of the ICC was submitted on June 22, 2015, to the Chief Execution Officer of the Authority. Therefore, it was clear that the appellant was not in the picture or involved in the dispute till the submission of the enquiry report of the ICC in June 2015.

Before the CAT, the counter affidavit was filed by the appellant in her official capacity as the Director, FSSAI, and the Presiding Officer, ICC.

"There is no criminal intent on the part of the appellant to cheat the complainant or wrongfully represent her in the proceedings before the Tribunal. Further, the question is whether, the actions of the appellant were during the course of her official duties only requiring sanction for prosecution," the bench said.

With regard to the issue of sanction for prosecution, the bench said, the test to decide whether sanction is necessary in a particular case is, whether the act is totally unconnected with the official duty or whether there is a reasonable connection with the official duty.

"The letter seeking sanction for prosecution is said to have been received by BIS only on 29.07.2022. By that time, the chargesheet had already been filed and the summoning order was issued by the Magistrate. Thereafter, BIS sought for further documents, including the FIR, and upon furnishing of the FIR and the chargesheet, BIS denied the sanction for prosecution of the appellant vide its letter dated 14.11.2022. This issue of sanction was decided by BIS within the stipulated period of four months," the bench said.

The court noted that the appellant was acting in her official duty, which was sufficient to hold that a prior sanction from the department was in fact necessary before the Magistrate taking cognizance against her.

"The Magistrate therefore erred in proceeding to take cognisance against the appellant without the sanction for prosecution being received from BIS, and since BIS has eventually refused to grant sanction for the prosecution of the appellant, the prosecution against the appellant could not have been sustained," the bench said.

Court also held that the argument advanced by the respondent-State and the complainant with respect to “deemed sanction” was also not tenable.

"Section 197 of CrPC does not envisage a concept of deemed sanction," the bench said.

The bench noted the chargesheet, as well as the counter affidavit of the respondent-State, have relied upon the judgment of the top court in Vineet Narain to contend that lack of grant of sanction by the concerned authority within relevant time would amount to deemed sanction for prosecution.

"However, a perusal of the said judgment reveals that it did not deal with Section 197 CrPC and rather it dealt with the investigation powers and procedures of Central Bureau of Investigation and Central Vigilance Commission. While it did mention that the time limits for grant of sanction for prosecution must be strictly adhered to, there is no observation to the effect that lack of grant of sanction for prosecution within the time limit would amount to deemed sanction for prosecution," the bench said.

Referring to reliance on the judgment in the Subramanian Swamy case to lend credence to the argument of deemed sanction for prosecution, the bench said, "Even the said judgment does not in any manner lay down the notion of deemed sanction."

First, the court said, the said judgment dealt primarily with the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 and the sanction for prosecution under that Act.

Secondly, the bench pointed out Justice G S Singhvi, while penning his separate but concurring opinion in the said judgment, had given some guidelines for the consideration of the Parliament, one of which was to the effect that at the end of the extended period of time limit, if no decision is taken, sanction will be deemed to have been granted to the proposal for prosecution, and the prosecuting agency or the private complainant will proceed to file the chargesheet/ complaint in the court to commence prosecution within fifteen days of the expiry of the time limit.

"However, such a proposition has not yet been statutorily incorporated by the Parliament and in such a scenario, this court cannot read such a mandate into the statute when it does not exist," the bench said.

Therefore, the court opined that the Magistrate was not right in taking cognizance of the offence against the appellant without there being a sanction for prosecution granted by the competent authority.

Further, it held that the high court erred in not considering the fact that the sanction for prosecution was not granted by the competent authority under Section 197 of the CrPC and eventually, the sanction was expressly denied by the competent authority with respect to the allegations against the appellant.

"The necessary sanction not having been granted has vitiated the very initiation of the criminal proceeding against the appellant herein," the bench said.

Consequently, the court quashed the chargesheet, the summoning order and the consequent steps, if any, taken by the trial court.

Case Title: Suneeti Toteja Vs State of UP & Another