Repeal Act Not Bound by Procedural Requirements As Original Law: SC

Court emphasised that it has been held on various instances that a Legislature may, subject to constitutional limitations, repeal any law it has enacted

The Supreme Court on February 6, 2025, said a repeal statute does not recreate the legal framework anew but rather extinguishes the earlier Act’s operative provisions so it is not subject to the same procedural requirements as an original enactment when it comes to the need for fresh presidential assent, provided that the repeal falls within the legislative competence of the State.

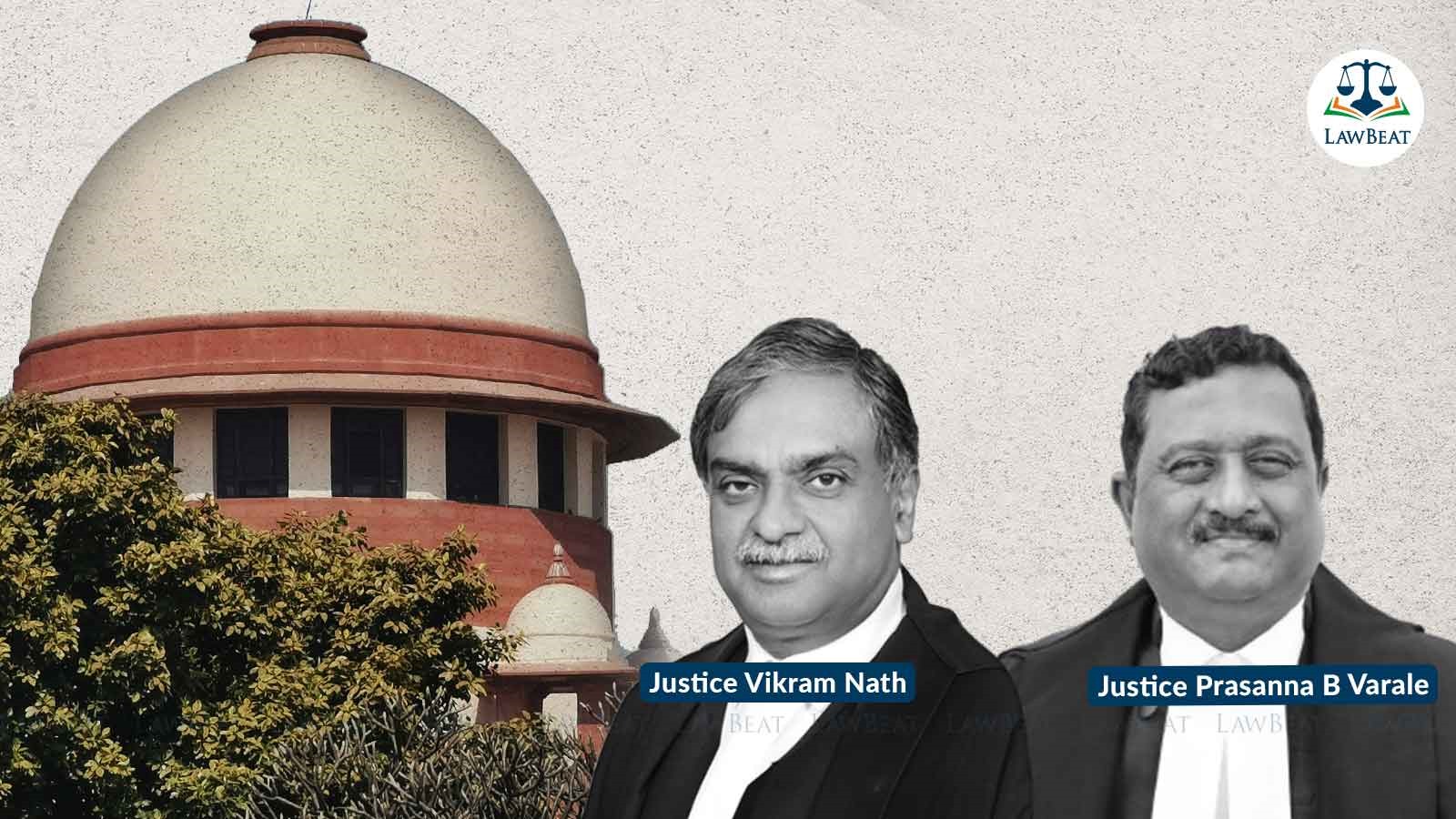

A bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Prasanna B Varale also said that the Supreme Court's previous decision which upheld the validity of the previous law, would mean merely affirming the constitutional validity of the statute at the time of its enactment; they do not bind the Legislature from modifying or repealing a statute when subsequent developments warrant a change in policy.

The bench pointed out it has been held on various instances by the top court that a Legislature may, subject to constitutional limitations, repeal any law it has enacted.

In Ramakrishna Vs Janpad Sabha (1962), it has been emphatically held that if the Legislature has the power to enact a law on a particular subject, it equally possesses the power to repeal that law, the court said.

In its judgment on a batch of civil appeals, the apex court concurred the Karnataka High Court's division bench's judgment of March 28, 2011, which upheld the 2003 Act repealing 1976 statute.

The 2003 Act repealed the Karnataka Contract Carriages (Acquisition) Act, 1976, which had acquired privately operated contract carriages and subsequently, the State Government transferred the vehicles and permits to State-owned Road Transport Corporations, notably including the KSRTC.

However, the 2003 Repeal Act was passed with the legislative intent to liberalise public transport, encourage private operators, and address “woeful shortages” in passenger services. The Legislature believed that removing the prohibitions would enable better competition, expand services, and ultimately bring greater passenger comfort.

Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) challenged the high court’s conclusion that repealing the 1976 Act was constitutional. It sought a declaration that the 2003 Repeal Act was invalid.

Dealing with the validity of the 2003 Repeal Act, the bench said it is well-settled principle that the power to repeal a law is coextensive with the power to enact it.

In this context, the court noted, the KCCA Act was enacted under Entry 42 of the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution and it received the assent of the President of India. The KCCA Act was designed to bring privately operated contract carriages under state control in order to serve the public interest and to implement the Directive Principles of State Policy, notably under Article 39(b) and (c).

"However, over the ensuing decades, the transport landscape in Karnataka underwent significant changes—urbanization intensified, public transport demand grew, and it became increasingly evident that the restrictive regime established by the KCCA Act was contributing to an artificial scarcity of public transport services, particularly in rural and semi-urban areas," the bench said.

In response to these evolving circumstances, the bench said, the Legislature exercised its plenary power by enacting the Karnataka Motor Vehicles Taxation and Certain Other Law (Amendment) Act, 2003, which repealed the KCCA Act.

"The repeal was not an arbitrary act of legislative whim but was backed by a clear statement of objects and reasons that identified the deficiencies in the existing regulatory framework and the necessity to liberalize the transport sector. The intention was to dismantle the statutory monopoly that the KCCA Act had created for the KSRTC and to open the door for private operators to address the burgeoning public transport needs," the bench said.

The KSRTC contended the repealing the KCCA Act was unconstitutional because it effectively overruled the decisions of the Supreme Court.

The apex court had upheld the validity of KCCA Act in State of Karnataka Vs Ranganatha Reddy (1978) and later reaffirmed in Vijayakumar Sharma Vs State of Karnataka (1990).

"In the subsequent decades, transport policy in Karnataka underwent shifts due to rising demand for public transport services, rapid urbanization, and the perceived inability of government-run corporations alone to meet commuter needs," the bench said.

Court said the 2003 Repeal Act is rooted in the practical realities of modern transport policy.

"The repeal of the KCCA Act was thus a deliberate policy decision aimed at fostering a more dynamic and responsive transport framework rather than an attempt to nullify well-established judicial pronouncements," it said.

The bench found the rationale underlying the 2003 Repeal Act was sound and consistent with the principles of legislative power.

"The arguments advanced by the respondent Corporation, that the repeal would amount to an impermissible overruling of prior Supreme Court decisions, that it violates the requirement of presidential assent, or that it is otherwise beyond the legislative competence of the State, are untenable," the bench said.

Court said the intent was to improve public transport services and to rectify the shortcomings of the earlier regulatory regime.

"Accordingly, we hold that Section 3 of the Karnataka Motor Vehicles Taxation and Certain Other Law (Amendment) Act, 2003, which repeals the KCCA Act, is constitutional," the bench said.

Court concluded that the State Legislature had rightly exercised its power to repeal the Act.

With regard to another issue, the bench also said the State Transport Authority has the power to delegate its functions, specifically, the issuance of contract carriage, special, tourist, and temporary permits, to its Secretary.

"Even if one accepts that the grant of permits has a quasi-judicial element, it is an established principle of administrative law that quasi-judicial functions may be delegated if the enabling statute expressly provides for such delegation. Here, Section 68(5) of the MV Act, coupled with the specific language of Rule 56(1)(d) of the KMV Rules makes it clear that the Legislature intended for the STA to delegate certain routine permit functions," the bench said.o

Court pointed out Secretary, being a high-ranking officer with substantial expertise in transport administration, is well equipped to handle routine permit applications.

"The delegation mechanism is not a blank check for arbitrary decision-making; it operates within the boundaries and conditions prescribed by the enabling rules framed under Section 96 of the MV Act. This ensures that, while administrative efficiency is achieved, there remains adequate oversight and accountability through the broader STA framework," it said.

Court did not agree to the high court's view that because permit-granting is quasi-judicial, it cannot be delegated to a single officer. "This view fails to recognise that delegation does not remove judicial oversight from the process. Instead, it merely streamlines routine functions that do not require the full deliberative process of the STA," the bench said.

The apex court held the high court's view in this regard as unsustainable in light of both legislative intent and practical necessity.

Case Title: M/s S R S Travels By Its Proprietor K T Rajashekar Vs The Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation Workers & Ors