Conduct of Arbitrators Must Match the High Standards Expected of Judges: SC

Court emphasised that arbitrators must meet even higher standards as their awards often carry greater acceptance and enforceability than court decisions, which are subject to appeals

The Supreme Court has said that arbitration, being quasi-judicial in nature, demands arbitrators to uphold impartiality and independence to a standard no less rigorous than what is expected of judges.

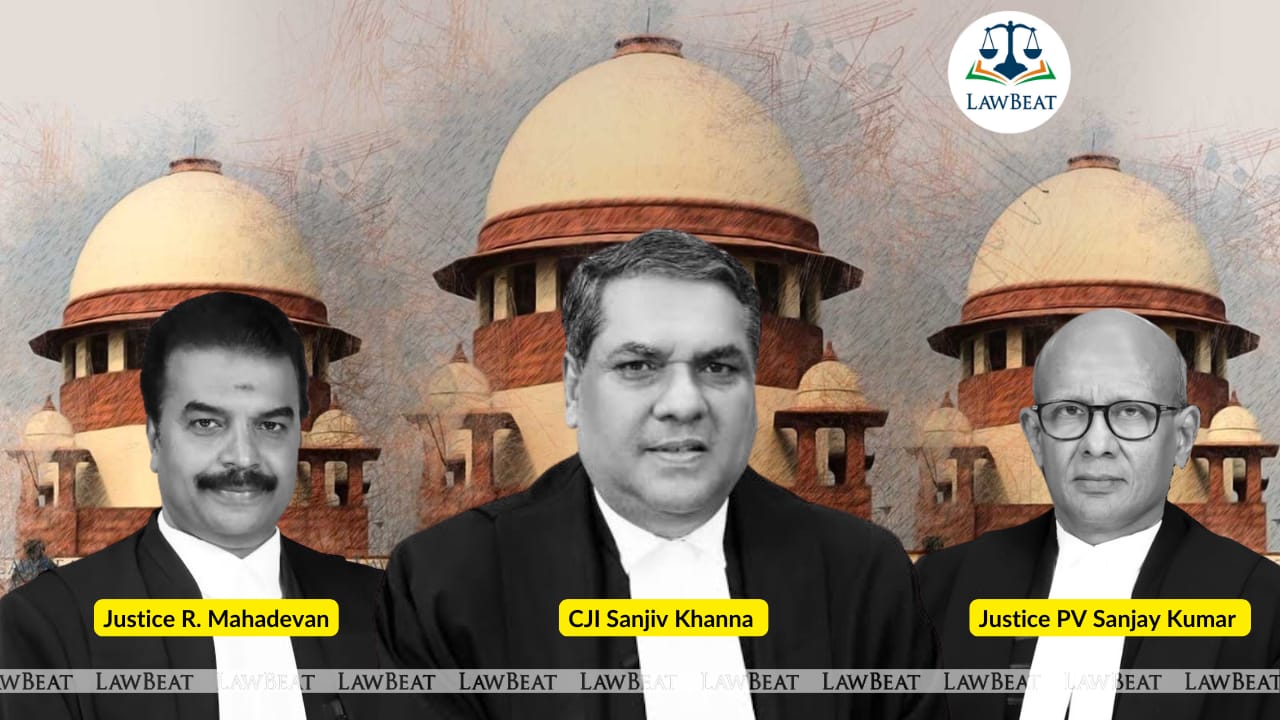

A bench of Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna and Justices Sanjay Kumar and R Mahadevan said arbitrators are expected to uphold a higher standard, as court decisions are subject to the collective scrutiny of an appeal, while an arbitration award typically enjoys greater acceptability, recognition, and enforceability.

Referring to Section 47 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, the court said, the provision, even at the stage of execution, permits a party to object to the decree, both on the grounds of fraud, as well as lack of subject matter jurisdiction.

On an appeal filed by the Uttar Pradesh government, the court held the arbitration proceedings were a mere sham and a fraud played by Respondent No 1, R K Pandey, by self-appointing or nominating arbitrators, who passed ex-parte and invalid awards.

"Pandey, is not a signatory to the purported arbitration agreement. Moreover, the parties thereto, DNPBID Hospital and the Governor of Uttar Pradesh, do not endorse any such agreement. From the cumulative facts and reasons, this is a clear case of lack of subject matter jurisdiction," the bench said.

Court allowed the state government's appeals and set aside two ex parte awards passed on February 15, 2008, and June 26, 2008.

"Both the Awards shall be treated as null and void and non-enforceable in law. Resultantly, the judgment passed, and the subject matter of the appeal shall be treated as set aside. The execution proceedings shall stand dismissed. The appellants will be entitled to costs of the entire proceedings as per the law," the bench said.

The state government filed an appeal against Allahabad High Court's division bench judgment of 2012.

Respondent Pandey was appointed as a lab technician in Dina Nath Parbati Bangla Infectious Disease Hospital located in Kanpur.

In 1956, the hospital was taken over by the state government and the entire staff was transferred to state government services. After the settlement was executed, the hospital became a unit of Ganesh Shanker Vidayarthi Memorial Medical College, Kanpur.

Pandey was informed that he would be superannuating on March 31, 1997. He was requested to contact the office along with pension papers and submit the same within one week so that the process can be initiated.

He filed a writ petition claiming he should retire at the age of 60 years, not at the age of 58 years.

The state government filed a response saying the minimum age for entering the government service is 18 years, and if a government servant retires at the age of 58 years, he would have completed 40 years of service.

In the present case, Pandey had completed service of 42 years of service. In other words, he would be 60 years of age.

Pandey, alongside, filed an arbitration suit before the District Judge, Kanpur Nagar, Kanpur, relying upon an alleged 1957 arbitration agreement between the then Administrator of the Hospital and the Governor of Uttar Pradesh. He said the dispute regarding his age of superannuation should be referred to arbitration.

The first ex-parte award in 2008 decreed the claim of Pandey for an amount of Rs 26,42,116 with interest at the rate of 18 % per annum. The award stated that Pandey had appointed the arbitrator and there was non-appointment by the opposite party and, therefore, Pawan Kumar Tewari, Advocate had acted as the sole arbitrator.

The second ex parte award in 2008 passed by Indivar Vajpayee awarded an amount of Rs 20,00,000 along with interest at the rate of 9% per annum in favour of Pandey.

On receiving notice in the execution petition, the state government filed objections against the two awards under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, and denied the authenticity of the documents.

The objections filed by the appellants under Section 34 of the A&C Act were dismissed by the trial court on the ground that they were barred by limitation and had been filed beyond the condonable period.

The High Court also dismissed the appeal on same grounds.

"We have narrated the facts in detail as they are peculiar, and intervention by this Court is necessary to prevent any attempt to enforce the so-called awards, which are null and void ab initio for several reasons," the apex court said.

The court cited Bilkis Yakub Rasool Vs Union of India and Others (2024), where it was ruled that fraud and justice never dwell together, and a litigant should not be able to benefit from a fraud practiced with an intention to secure him an illegal benefit.

In the present case, the bench said, the so-called arbitration agreement was nowhere available on the records of either the Municipal Corporation or the State of Uttar Pradesh. Pandey did not file the original agreement since he was not in possession of the same, nor was he a signatory and party to the arbitration agreement.

"An arbitration agreement is sine qua non for arbitration proceedings, as arbitration fundamentally relies on the principle of party autonomy; - the right of parties to choose arbitration as an alternative to court adjudication. In this sense, ‘existence’ of the arbitration agreement is a prerequisite for an award to be enforceable in the eyes of law," the bench said.

No doubt, Section 7 of the A&C Act, which defines the ‘arbitration agreement’, is expansive and includes an exchange of statements of claim and defence in which the existence of the agreement is alleged by one party and not denied by the other party, albeit the existence of the arbitration agreement is not accepted by either the Municipal Corporation or the Appellant, the State of Uttar Pradesh, the bench added.

In the case, the court said, there was no evidence to show the existence of the arbitration agreement, except a piece of paper, which was not even a certified copy or an authenticated copy of the official records.

"How and from where Pandey, got a copy of the agreement, and that too nearly 10 years after his retirement and filing of a writ petition remains unknown," the bench wondered.

Court held that the unilateral appointment of the arbitrator Pandey was, therefore, contrary to the arbitration clause as propounded by him.

Case Title: State of Uttar Pradesh And Another Vs R K Pandey And Another