State can't claim adverse possession over property of own citizens: SC

Court said that allowing the State to appropriate private property through adverse possession would undermine the constitutional rights of citizens and erode public trust in the government

The Supreme Court recently observed that the State cannot claim adverse possession over the property of its own citizens as allowing the State to appropriate private property through adverse possession would undermine the constitutional rights of citizens and erode public trust in the government.

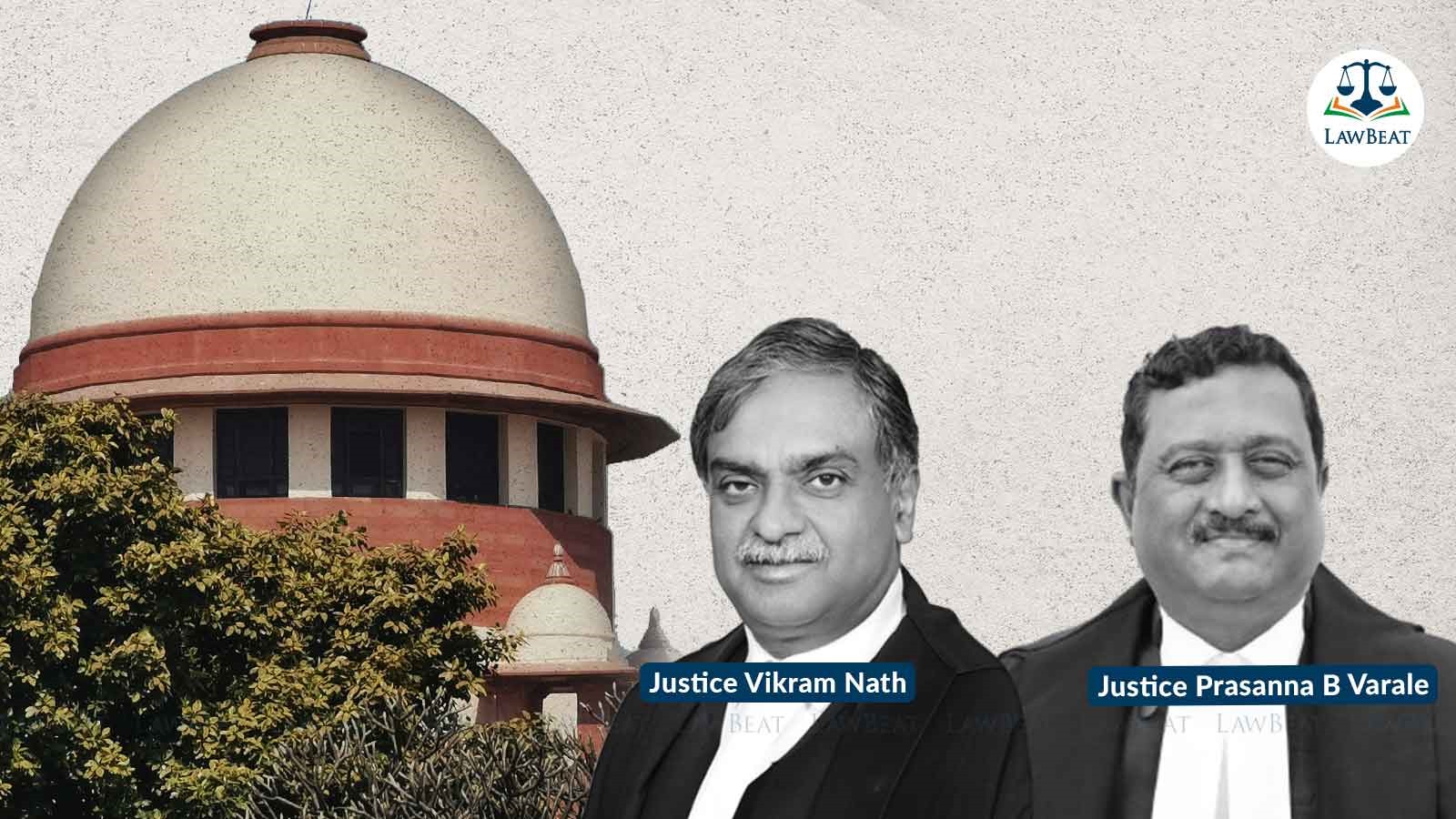

A bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Prasanna B Varale emphasised that adverse possession requires possession that is continuous, open, peaceful, and hostile to the true owner for the statutory period.

The apex court dismissed an appeal by the Haryana government against the Punjab and Haryana High Court's judgment of January 31, 2019, allowing a regular second appeal by respondents Amin Lal, since deceased, through his legal representatives and others.

The High Court had set aside the decision of the first appellate court and restored the decree passed by the trial court in favour of the plaintiff.

The dispute pertained to a piece of land measuring 18 Biswas Pukhta, situated within the revenue estate of Bahadurgarh, Haryana. The land is located on both sides of National Highway No 10, which connects Delhi and Bahadurgarh.

In 1981, the plaintiff claimed ownership of the land based on revenue records and alleged that the defendants had unauthorisedly occupied the land approximately three and a half years prior to the filing of the suit.

The State Government claimed that it had been in continuous and uninterrupted possession of the suit land since 1879-80. It claimed that its possession was open, hostile, and adverse to the plaintiffs, and as such, it had become owners by way of adverse possession.

It also contended that the land had been used as a store by the PWD and its predecessor entities, including the District Board and Zila Parishad, for over a century.

The trial court held that the defendants had failed to prove that they had become owners by adverse possession. Mere placement of bitumen drums and construction of a boundary wall in 1980 did not constitute adverse possession, it opined. The first appellate court allowed the appeal by the State.

The High Court allowed the appeal by the plaintiff, holding the State cannot claim title through adverse possession against its own citizens and the defendants failed to specifically deny the plaintiffs' title as required under Order 8 Rule 5 of the Code of Civil Procedure. It further said the possession of the defendants was permissive, as evidenced by the Misal Hakiyat of 1879-80.

Examining the issue of whether the High Court was correct in setting aside the judgment of the first appellate court and restoring the decree passed by the trial court in favour of the plaintiffs, the bench found as unconvincing and misplaced the State's contention that the plaintiff failed to prove their title and ownership.

The court pointed out that by asserting adverse possession, the appellants had impliedly admitted the plaintiffs' title. It noted that the plaintiffs relied on jamabandi entries to establish their ownership. The jamabandi for the year 1969-70 recorded the name of Amin Lal as owner to the extent of half share.

"Revenue records are public documents maintained by government officials in the regular course of duties and carry a presumption of correctness under Section 35 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872. While it is true that revenue entries do not by themselves confer title, they are admissible as evidence of possession and can support a claim of ownership when corroborated by other evidence," the bench said.

The court also noted that the plaintiffs had produced registered sale deeds and mutation records as part of the additional documents.

It also found the appellants did not dispute the plaintiffs' title in their pleadings or during the trial.

"The first appellate court's finding that the plaintiffs are not the true owners is based on conjecture and lacks evidentiary support. The appellants cannot now, at this appellate stage, challenge the plaintiffs' ownership without having raised a specific denial earlier," it said.

With regard to the State's claim that the burden of proof lay on the plaintiffs to establish their title, the bench said, "It is a well-settled principle that in a suit for possession based on title, the plaintiffs must establish their ownership."

In the present case, the court said, the plaintiffs had done so by producing revenue records and, subsequently, the registered sale deeds and mutation entries. Furthermore, as the appellants failed to deny the plaintiffs' title specifically and instead relied on adverse possession, the burden has shifted to the appellants to prove their adverse possession. In the case, the plaintiffs have sought possession based on their title, which they have established through documentary evidence, the top court opined.

It also held that the appellants claim that due to their long and continuous possession of the suit property since 1879-80, they had perfected their title, was also not sustainable in law.

"However, it is a fundamental principle that the State cannot claim adverse possession over the property of its own citizens," the bench said.

"Allowing the State to appropriate private property through adverse possession would undermine the constitutional rights of citizens and erode public trust in the government. Therefore, the appellants' plea of adverse possession is untenable in law," the bench said.

The court also said the appellants' acts such as placing bitumen drums, erecting temporary structures, and constructing a boundary wall in 1980 did not constitute adverse possession.

"Adverse possession requires possession that is continuous, open, peaceful, and hostile to the true owner for the statutory period. In this case, the appellants' possession lacks the element of hostility and the requisite duration," the bench said.

The appellants last contention that the High Court overstepped its jurisdiction under Section 100 of the Code of Civil Procedure by reappreciating evidence and interfering with findings of fact also has no legs to stand, the court opined.

The court pointed out the High Court had framed substantial questions of law regarding whether the State can claim adverse possession against its own citizens and whether taking the plea of adverse possession implies admission of the plaintiffs' title. These are substantial questions of law that justify the High Court's interference, it said.

The High Court found that the first appellate court had ignored material evidence and legal principles, leading to a perverse judgment. Therefore, the High Court was justified in exercising its jurisdiction under Section 100 of the Code of Civil Procedure, the bench held.

In the case, the court said that the findings of the first appellate court's judgment were flawed for various reasons as it erroneously placed the burden of proving ownership on the plaintiffs, despite the defendants' admission of their title by pleading adverse possession.

The court disregarded the jamabandi entries and other revenue records without valid justification, the bench said.

"The court's conclusion that the plaintiffs are "land grabbers" is not supported by evidence and appears to be based on conjecture. Therefore, the High Court rightly set aside the first appellate court's judgment, which suffered from legal infirmities and misappreciation of evidence," the bench said.

The court thus found no merit in the appellants' contentions, holding the High Court's judgment was based on sound legal principles and correct appreciation of evidence.

"The plaintiffs have established their ownership of the suit property, and the State cannot claim adverse possession against its own citizens," the bench said, dismissing the State's appeal.

Case Title: The State of Haryana & Anr Vs Amin Lal (Since Deceased) Through His LRs & Ors