Limitation Provisions to Be Liberally Interpreted To Let Parties Avail Limited Remedies Under A&C Act: SC

Court said if limited remedy is denied on stringent principles of limitation, it will cause great prejudice

The Supreme Court has said the substantive remedies available under Sections 34 and 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act (A&C Act) are, by their very nature, limited in their scope due to statutory prescription, therefore it is necessary to interpret the limitation provisions liberally, or else even the limited window available to parties to challenge an arbitral award will be lost.

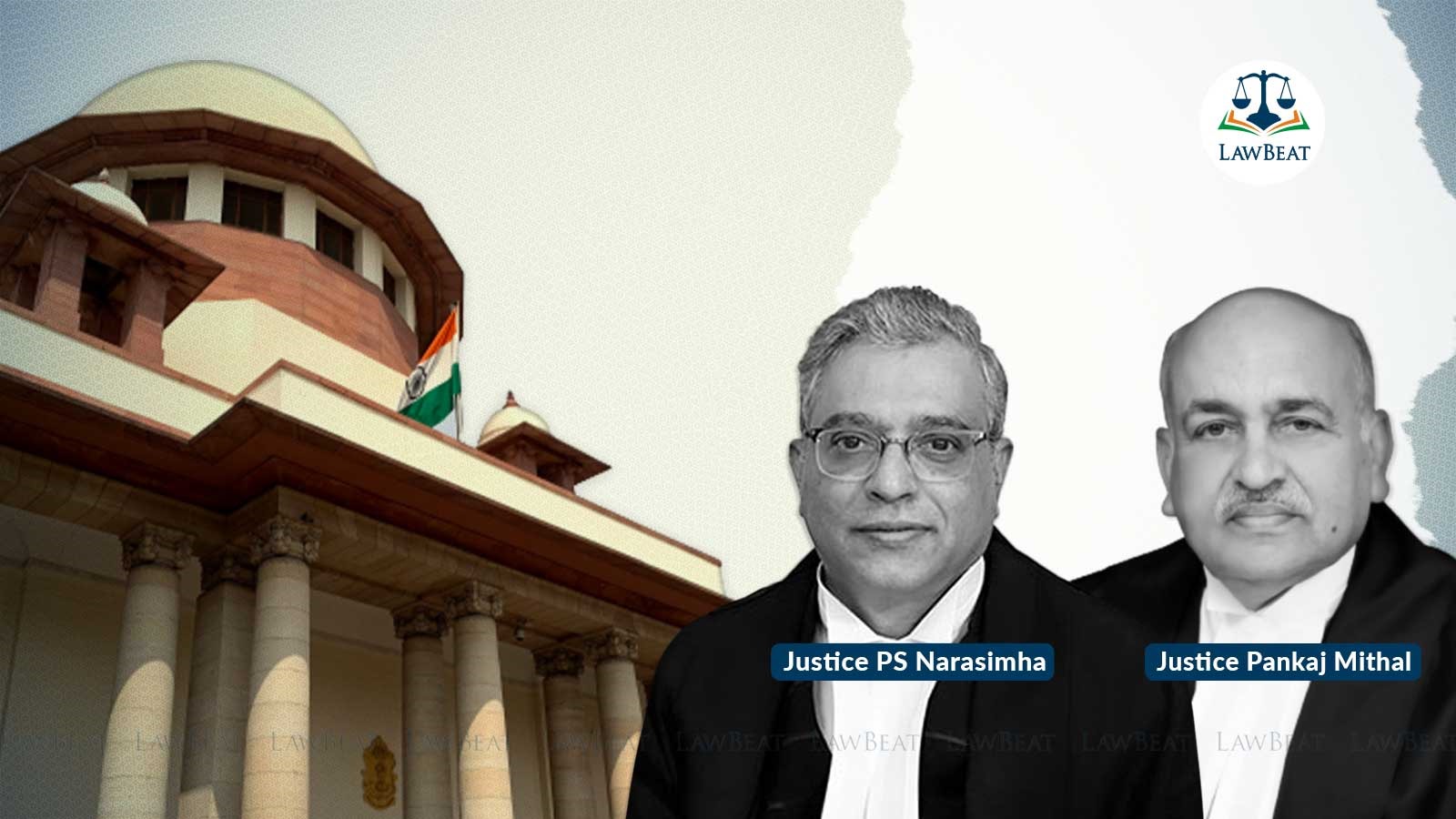

A bench of Justices P S Narasimha and Pankaj Mithal said the remedy under Section 34 is precious, and courts will keep in mind the need to secure and protect such remedy while applying limitation provisions.

"If this limited remedy is denied on stringent principles of limitation, it will cause great prejudice and has the effect of denying the remedy, and in the long run, it will have the effect of dissuading contracting parties from seeking resolution of disputes through arbitration. This is against public policy," the bench said.

The court was dealing with a civil appeal filed by My Preferred Transformation & Hospitality Pvt Ltd & Anr. The appellants received the arbitral award on February 14, 2022. The 3-month limitation period for filing the application under Section 34(3) of the A&C Act expired on May 29, 2022, on which date the court was functioning, but closed after five days for vacation commencing from June 04, 2022 to July 03, 2022. The application under Section 34 was filed immediately on the court’s reopening, i.e. July 04, 2022.

The Delhi High Court's single judge under Section 34 and the division bench under Section 37 dismissed the petition as barred by limitation.

Thus, the issue before the apex court was whether the benefit of the additional 30 days under the proviso to Section 34(3), which expired during the vacation, could be given when the petition was filed immediately after reopening in exercise of power under Section 4 of the Limitation Act, 1963.

The bench dismissed the appeal after considering Sections 34(3) and 43(1) of the A&C Act, Sections 4 and 29(2) of the Limitation Act and Section 10 of the General Clauses Act, 1897, as well as precedents of the court.

The court held there was no wholesale exclusion of Sections 4 to 24 of the Limitation Act when calculating the limitation period under Section 34(3) of the A&C Act.

"Section 4 of the Limitation Act applies to Section 34(3) of the A&C Act only to the extent when the 3-month period expires on a court holiday. It does not aid the applicant when the 30-day condonable period expires on a court holiday. In view of the applicability of Section 4 of the Limitation Act to Section 34 proceedings, Section 10 of the GCA does not apply and will not benefit the applicant when the 30- day condonable period expires on a court holiday," the bench said.

In his judgment, Justice Narasimha, however, said, the statutorily prescribed period under Section 34(3) of the A&C Act is 3 months, and an additional 30 days.

"In our opinion, it will be wrong to confine the period of limitation to just 3 months by interpreting it as the “prescribed period” and excluding the balance 30 days under the proviso to Section 34(3) as not being the prescribed period through a process of interpretation," he said.

The judge noted the applicability of provisions from Sections 4 to 24 of the Limitation Act and the manner in which they apply are at its doorstep, rather than being determined by a clear and categorical statutory prescription.

"This is perhaps the reason why the Parliament has used the expression “express exclusion” in Section 29(2) of the Limitation Act. We are conscious of the fact that it is too late in the day to hold that “express exclusion” will not include implied exclusion. It is for the legislature to take note of this position and bring about clarity and certainty. We say no more, for the overbearing intellectualisation of the Act by courts has become the bane of Indian arbitration," Justice Narasimha wrote.

Concurring with Justice Narasimha's views, Justice Mithal opined the statutes ought not to provide different period of limitation for instituting suit, preferring appeal and making an application, rather all statutes should stick to a uniform period of limitation say 90 days for preferring Special Leave Petition/Appeal to the Supreme Court of India. The courts should also be empowered to condone the delay if sufficient cause is shown for not filing it within the time prescribed rather than restricting the condonable period to a fix period of 15 days or 30 days as provided in some of the statutes, he said.

He suggested to the law makers to keep this in mind while enacting new Acts and ensure that uniform system is applied in all enactments, be it present or future.

"Practically all new/recent enactments are deviating from the prescribed period of limitation as per the Schedule of the Limitation Act and are generally prescribing its own period of limitation as under the A & C Act itself. At the same time, statutes further provide that the delay beyond a certain period cannot be condoned by the court. This is obviously in deviation to what is prescribed by Section 5 of the Limitation Act," he said.

This deviation and restriction, Justice Mithal said, create confusion and ordinarily even a lawyer at times fails to notice that a different period of limitation has been prescribed for preferring an appeal under a particular statute.

"Moreover, there may be genuine cases where the litigant may not be able to approach the court in time for cogent reasons beyond his control," he said.

Giving an example, Justice Mithal said, in arbitration matters where an award is passed on a particular date and a copy of it is also served upon the litigating party but that party happens to be seriously ill and hospitalised for months together and as such is unable to prefer a petition under Section 34 within the period of limitation prescribed.

"If the delay in challenging the award is not condoned beyond the period of 30 days, he would suffer great prejudice and may lose the remedy on a technical ground even though he may be having a good case on merit. There may also be a situation where a litigant is facing proceedings by the law enforcement agencies like the Enforcement Directorate, Central Bureau of Investigation, etc., and is taken into custody and as such is unable to take the legal remedy within the period of limitation prescribed. He avails the remedy only after he is out of custody; months after the service of the order," he said.

In such circumstances, Justice Mithal suggested the legislature ought not to confine condoning the delay only for a prescribed period and not beyond it. Rather it should follow the principle of condoning the delay as enshrined under Section 5 of the Limitation Act.

"This would not only avoid a good case to be thrown out on the ground of limitation but at the same time would bring about uniformity in law," he said.

Case Title: MY PREFERRED TRANSFORMATION & HOSPITALITY PVT. LTD. & ANR VERSUS M/S FARIDABAD IMPLEMENTS PVT. LTD