'Encroachment on RBI's Domain,' SC Sets Aside NCDRC Order on Ceiling on Credit Card Dues

Court said a policy decision pertaining to the rate of interest, and trade practices carried out by the banks across the country, is a regulatory function within the specific statutory domain of the Reserve Bank of India and cannot come under the purview of judicial scrutiny by the National Commission

The Supreme Court on December 20, 2024, set aside a 2008 decision by the National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission which unilaterally held that any interest above 30% per annum on credit card dues as usurious and unfair trade practice.

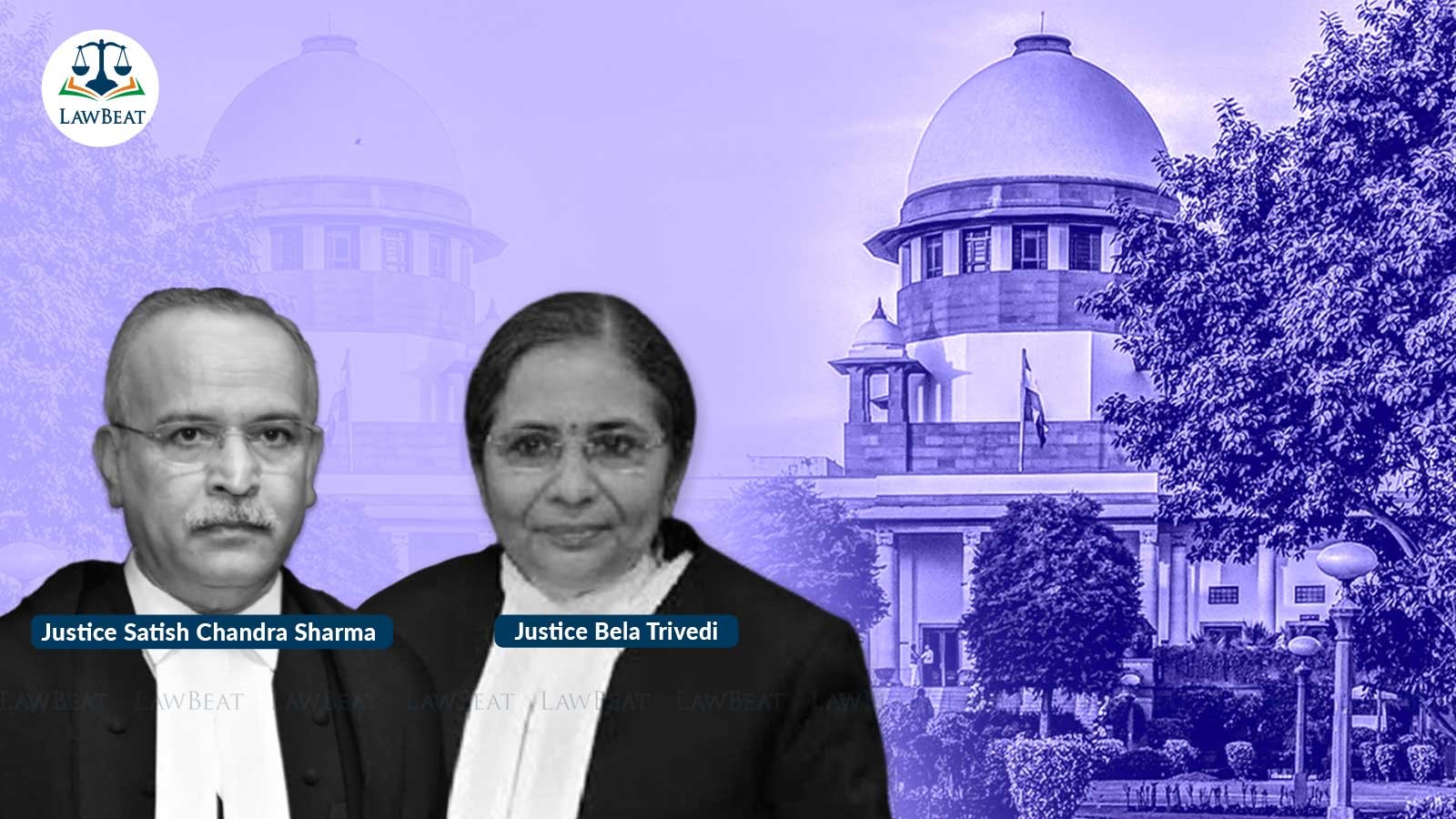

A bench of Justices Bela M Trivedi and Satish Chandra Sharma held that administrative policy decisions of banks, do not constitute provisions/facilities of banking, which may come under the umbrella of ‘service’, defined under section 2(1)(o) of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986.

"A policy decision pertaining to the rate of interest, and trade practices carried out by the banks across the country, is a regulatory function within the specific statutory domain of the Reserve Bank of India and cannot come under the purview of judicial scrutiny by the National Commission," the bench said.

Court said that the July 7, 2008 order by the consumer panel was contrary to the legislative intent of section 21A of the Banking Regulation Act and was an encroachment upon the domain of the Reserve Bank of India.

Allowing a batch of appeals filed by HSBC and others, the bench said that the credit card holders in the present case were well-informed and educated and had agreed to be bound by the express stipulation by the terms issued by the respective banks.

The banks have provided all necessary information with regard to fees, and charges applicable to credit cards, credit and cash withdrawal limits, it pointed out.

"We are of the considered opinion that once the terms of the credit card operations were known to the complainants and disclosed by the banking institutions before the issuance of the credit cards, the National Commission could not have scrutinized the terms or conditions, including the rate of interest," the bench said.

The court also found the respondent NGO Awaz and others had not approached the statutory authority, the Reserve Bank of India, for any objection against the rate of interest, or the high Benchmark Prime Lending Rate.

The court emphasized the requirement of obtaining prior permission from the Commission, for any consumer to act in a representative capacity, which in no way can be dispensed with.

It also pointed out that a trust, whether registered under the Indian Trust Act, or the State Trust Registration Act, is not a “person” as defined under Section 2(1)(m) of the Consumer Protection Act.

The bench further held, "We are of the considered opinion to re-agitate the terms and conditions of credit card facilities provided by the banks, and re-write the terms thereof, including the rates of interest charged by the banks, is exorbitant, however reasonable, is an attempt by the National Commission to constitute a new contract, which is impermissible in law".

The court pointed out it is a settled cannon of law, that a contract, being a creature of an agreement between two or more parties, is to be interpreted giving the actual meaning to the words contained in the contract and it is not permissible for the court to make a new contract, however reasonable, if the parties have not made it themselves.

In the present context, the court noted, the pre-conditions of ‘deceptive practice’ and unfair method’ were manifestly absent.

The bench pointed out whether an act can be condemned as an unfair trade practice, or not, the key is to examine the ‘modus operandi’ i.e. whether there is any false statement/ misrepresentation, or deception.

"The banks have in no manner made any misrepresentation, to deceive the credit card holders. Upon availing the facility of the credit cards, the customers, are made aware of ‘the most important terms and conditions’, including the rate of interest, that shall be charged by the Banks," the bench said.

Even on merits, the bench said, the Reserve Bank of India, had made it clear that there existed no material on record, to establish that any bank had acted contrary to the policy directives issued by the RBI.

"Even otherwise, there is not even a single averment so as to establish how the charging of rates of interest upon the default by credit card holders, without a standardized rate, is usurious and constitutes an unfair trade practice. The mere inflation in the rates of interest cannot be construed as a practice, intended to cause loss or injury," the bench said.

Although, the court agreed that the National Commission had been duly empowered under the statute to set aside unfair contracts, which may symbolise a single will or are unilaterally dominant or incorporate terms which are unfair and unconscionable.

"However, the rate of interest, charged by the banks, determined by the financial wisdom and directives issued by the Reserve Bank of India, and is duly communicated to the credit card holders from time to time, cannot be in any manner unconscionable or unilateral. The credit card holders are duly educated and made aware of their privileges and obligations, including timely payment and levying of penalty on delay," it said.

The court also agreed to a contention by the RBI that there was no question of the banking regulator being directed to impose any cap on the rate of interest, either on the banking sector as a whole, or in respect of any one particular bank, contrary to the provisions contained in the Banking Regulation Act, and the circulars/directions issued thereunder.

The appellants, Hong Kong Shanghai Corporation, Citibank, American Express Banking Corporation, Standard Chartered Bank, Housing Development Finance Corporation had challenged the correctness of the impugned order, whereby the National Commission had held that the charging of interest at rates beyond 30% by the banks/non-banking financial institutions, from credit card holders, upon delay or default in payment, constituted an unfair trade practice and that penal interest could be charged only once for one period of default and the same could not be capitalised.

They contended that determining the reasonability and ‘fixing of the maximum or the minimum rates of interest’, was the exclusive function of the RBI, a statutory authority responsible for the regulation of the Indian Banking system.

The banks also relied upon the statutory bar under section 21A & 35A of the Banking Regulation Act, for courts/tribunals to re-open transactions between banks, on the question that the rates of interest are excessive. The law empoweres the Reserve Bank of India, to formulate directions, as befitting the public interest, proper management and banking policies of the country, they said.

The appellants said that the encroachment of this statutory domain of the Reserve Bank of India, by the National Commission, was against the mandate of the Constitution and the legislative intent of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934.

They also said that the original complaint not only failed to meet the criterion of a complaint u/s 12 r/w 13 of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986, but was a public interest litigation, guised as a consumer dispute which could not have been entertained by the National Commission, being beyond its inherent jurisdiction.

On the opposite, the complainant said that the rates of interest charged by the banks from its credit cardholders was usurious and exploitative in nature, and in contravention of the circulars issued by the Reserve Bank of India. They claimed that they represented the public at large, as a voluntary consumer association voicing against the usurious rate of interest charged by the banks, which was a deficiency in service in banking and constituted an unfair trade practice, in terms of the Consumer Protection Act, 1986.

There ought to have been a notification passed by the Reserve Bank of India fixing a maximum ceiling rate of interest for all banks, and in pursuance thereto had approached the National Commission by filing the consumer complaint, they said.

RBI, however, submitted that there was no question of it being directed to impose any a cap on the rate of interest either on the banking sector as a whole, or in respect of any one particular bank, contrary to the provisions contained in the Banking Regulation Act, and the circulars/directions issued thereunder.

In terms of the regulatory guidelines issued vide Master Direction-Credit Card & Debit Card-Issuance and Conduct dated April 21, 2022 as on March 07, interest charged on credit cards shall be justifiable having regard to the cost incurred and the extent of return that could be reasonably expected by the card user, it said.

The National Commission is bound to accept the policy contained in the circulars as valid and cannot question the policy decision, the regulator said.

In its judgment, the top court held that the complaint failed to meet the threshold of Sections 12(1) and 13 of the Act.

The court also said the consumer complainant failed to disclose any deficiency in service or violation and was in fact a public interest litigation in guise of a purported consumer dispute.

The court also said a direction by the National Commission or any other court, must be based on material or evidence and not on surmises, and bald averments made by complainants.

"We are thus unable to subscribe to the view adopted by the National Commission, that ‘any complaint under the Consumer Protection Act, 1986 to curb unfair trade practice(s) adopted by the banks is maintainable’," the bench said.

The court said the National Commission had assumed jurisdiction and expertise over the Reserve Bank of India, whilst observing that a ceiling on the rates of interest was the purported solution to the alleged exploitation of credit card holders.

Case Title: Hongkong And Shanghai Banking Corp Ltd Vs Awaz & Ors