SC Acquits Man in Murder Case Over Glaring Inconsistencies in Recoveries

SC opined that the courts below were not justified in disregarding the glaring inconsistencies with respect to the recoveries made by the police pursuant to the alleged disclosure made by the appellant-accused

The Supreme Court, on February 7, 2025, acquitted a man in a murder case, citing glaring inconsistencies in the prosecution’s case. It highlighted that the case relied solely on circumstantial evidence, with no eyewitness testimony or judicially admissible confession to support the charges.

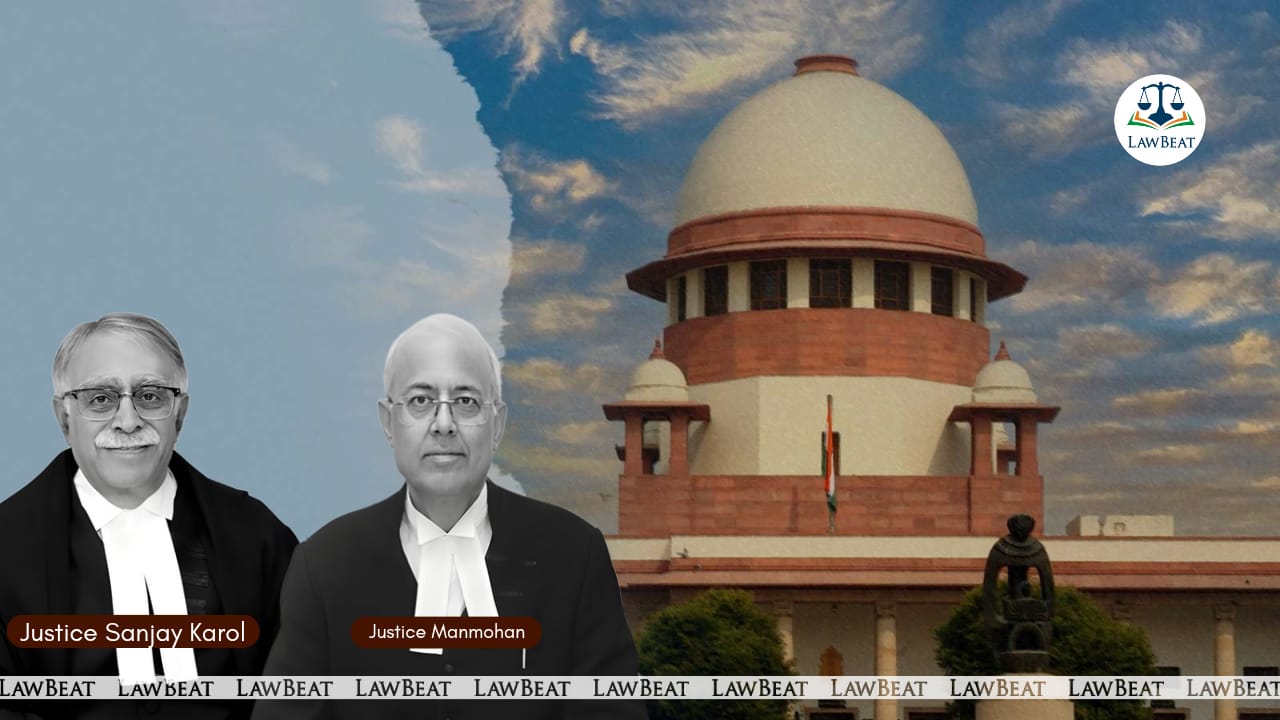

A bench of Justices Sanjay Karol and Manmohan gave benefit of doubt to appellant Raza Khan by setting aside his conviction and sentence of life term awarded by Raipur's sessions court and affirmed by the Chhattisgarh High Court.

It was the prosecution's case that the appellant accused had borrowed money from deceased Neeraj Yadav and a dispute had arisen between them with respect to the refund of the borrowed amount.

It was alleged that the appellant-accused along with co accused Tarachand Verma (acquitted by the trial court) had taken the deceased on the intervening day of November 29, 2013 in an auto to the place of incident and assaulted the deceased with an iron pipe and battleaxe (Gandasa) and thereby committed his murder and with intent to cause disappearance of evidence smashed his head with stone and after removing his full pant tied a rope around his waist and thrown the body in the water of a quarry.

The police claimed that it had made recovery and seizure of two gold chains of the deceased from the rooftop of the house of the appellant-accused. The prosecution also examined Bhagwat Prasad Sahu and Balram Yadav, who had deposed that the deceased was seen travelling with the appellant-accused in an auto on November 29, 2013 between 5:00 PM and 6:00 PM.

Having heard the counsel for the appellant-accused and the State, the bench said, it is well settled law that where the case rests entirely on circumstantial evidence, the chain of evidence must be so far complete, such that every hypothesis is excluded but the one proposed to be proved and such circumstances must show that the act has been done by the appellant-accused within all human probability. In this regard, the bench cited Hanumant Vs State of Madhya Pradesh (1952) and Sharad Birdhichand Sarda Vs State of Maharashtra (1984).

In the case, the bench noted, to prove the charges, the prosecution had laid emphasis on recovery of weapon of assault (stone as well as the gandasa) and gold chains belonging to the deceased, on the basis of statement given by the appellant-accused while in custody.

In this regard, the court pointed out, Sections 25 and 26 of the Evidence Act stipulate that a confession made to a police officer is not admissible. However, Section 27 is an exception to Sections 25 and 26 and serves as a proviso to both these sections.

"This court is of the view that Section 27 lifts the ban, though partially, to the admissibility of confessions. The removal of the ban is not of such an extent so as to absolutely undo the object of Section 26. As such the statement whether confessional or not is allowed to be given in evidence but that portion only which distinctly relates to discovery of the fact is admissible. A discovery of a fact includes the object found, the place from which it is produced and the knowledge of the appellant-accused as to its existence," the bench said, relying upon Udai Bhan Vs State of Uttar Pradesh, (1962).

"In the present case, the prosecution has produced Tirath Dhruv and Bhuvan Dhimar as the panch witnesses to prove the recovery pursuant to the disclosure made by the Appellant-accused. However, a bare perusal of the testimonies of the said witnesses raises serious doubts regarding the version of the prosecution with respect to the alleged disclosure made by the appellant-accused herein and the recoveries pursuant to such alleged disclosure", the bench noted.

It pointed out that the said witness admitted that the Memoradum of Statement of the appellant-accused had been taken and he signed the same on the instructions of the police, without reading or understanding the contents of the said document. He admitted that none of the seizure memos were prepared or signed at the spot. He stated that the same were prepared and signed at the police station.

"Therefore, from the testimony of Tirath Dhruv, there is grave doubt as to whether the appellant-accused had made any disclosure in front of the said witness or that any alleged recovery had in fact been witnessed by Tirath Dhruv," the bench said.

The court found that there were glaring inconsistencies with respect to the manner in which gold chains were recovered from the house of the appellant-accused and further, the presence of the appellant-accused at the time of the said recovery was itself doubtful.

Similarly, the bench said, "There are also glaring inconsistencies in the TIP of the gold chains rendering the proceedings unreliable and inadmissible, as Anwar Hussain (who identified the two gold chains) has consistently denied that Purnima Yadav (wife of the deceased) identified the two gold chains and that the said gold chains belonged to the deceased. He further denied that six more similar chains were placed alongside the said two gold chains. This fact has been corroborated by the testimonies of Gopi Sahu and Yugal Kishore Verma, wherein they have stated that only two gold chains were placed for identification".

Further, the testimonies of witnesses reveal that the two gold chains do not bear any distinguishable mark or properties and no identification mark or properties were disclosed by Purnima Yadav prior to identification proceedings, the bench highlighted.

The bench thus said, "This court is of the view that the courts below were not justified in disregarding the glaring inconsistencies with respect to the recoveries made by the police pursuant to the alleged disclosure made by the appellant-accused. Consequently, the manner of recovery and preparation of seizure memos raises grave doubts about the version of disclosure and recovery put forth by the prosecution."

The bench held that the prosecution had failed to prove the chain of circumstances leading to the guilt of the accused, beyond reasonable doubt.

Therefore, it finally allowed the appeal and directed for forthwith release of the appellant-accused, unless and until he was in detention in another case.

Case Title: Raja Khan Vs State of Chhattisgarh