AYUSH Doctors as Registered Practitioners? Supreme Court Seeks Centre's Response on PIL

The Supreme Court on Monday sought responses from the Union Ministries of Law, Health, and AYUSH on a public interest litigation (PIL) seeking recognition of AYUSH doctors as ‘Registered Medical Practitioners’ (RMPs) under Indian law, similar to their allopathic counterparts.

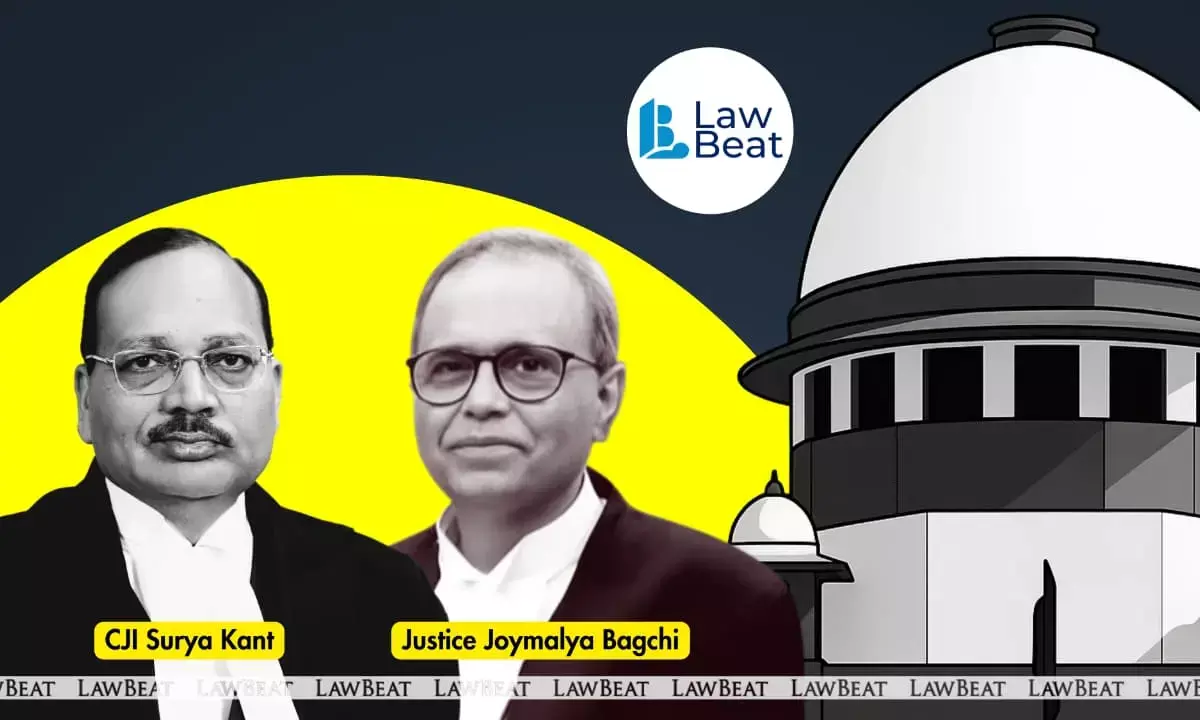

The Bench of Chief Justice Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi issued notices after hearing Advocate Ashwini Upadhyay, who appeared for the petitioner, his son, law student Nitin Upadhyay.

The Bench took the plea on record in a lighter vein, with the CJI remarking, “Is he your son?” When Upadhyay replied in the affirmative, the CJI quipped, “We thought he will get some gold medal etc., but he is filing PILs now. Why don’t you study? Issue notice. Only for your son, so that he studies well.”

The PIL urged the Court to declare that AYUSH doctors fall within the definition of ‘Registered Medical Practitioners’ under Section 2(cc) of the Drugs and Magic Remedies (Objectionable Advertisements) Act, 1954 (DMR Act), which regulates medical advertisements and prohibits misleading claims about drugs and remedies.

The petition, filed through Advocate Ashwani Kumar Dubey, also sought the constitution of an expert committee to review and update the Act’s provisions in line with modern scientific and evidence-based developments.

According to the plea, the DMR Act; intended to curb false medical claims, has now created an unintended blanket ban on legitimate advertisements by AYUSH practitioners, who are often excluded from its definition of recognised medical professionals.

“The Act was enacted to protect the public from false and misleading medical advertisements. However, Section 3(d) imposes a complete ban on advertisements relating to certain diseases and conditions,” the plea stated, arguing that this restriction suppresses truthful, scientific, and lawful information about alternative medical treatments.

Highlighting that the last substantive amendment to the DMRA was made in 1963, the petition notes that there have been significant advancements in medical science, diagnostics and public health awareness since then. It alleges that no expert committee has ever been constituted to periodically review or update the Schedule to the Act, rendering its continued application constitutionally obsolete under the doctrine of updating construction.

The petitioner further contends that the impugned provisions violate Articles 19(1)(a) and 19(1)(g) by suppressing truthful medical information and imposing unreasonable restrictions on the right of medical practitioners to practise their profession. Reliance has been placed on Chintaman Rao v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1951) to argue that the blanket prohibition under Section 3(d) fails the test of reasonableness and proportionality.

It is also argued that the Act infringes Article 21 by denying citizens access to information necessary to make informed healthcare choices, an essential component of the right to health and to live with dignity. The plea cites Francis Coralie Mullin v. Administrator, UT of Delhi (1981) to submit that a law suppressing medical awareness without proportional justification cannot be sustained.

Invoking Article 51A(h), the petitioner asserts that continued enforcement of the DMRA obstructs the development of scientific temper and the spirit of inquiry. Reference has been made to Mirzapur Moti Kureshi Kassab Jamat (2005) to underline that fundamental duties are relevant while assessing the reasonableness of restrictions on fundamental rights.

The petition emphasises that AYUSH systems are cost-effective, preventive in nature, and relied upon by large sections of the population. Silencing statutorily recognised AYUSH practitioners, it argues, undermines public health and deprives citizens of access to lawful medical options.

The petitioner has therefore sought directions to read down Section 3(d) to permit bona fide medical advertisements by duly registered practitioners, including AYUSH practitioners, or alternatively to strike it down. A further prayer has been made to widen the definition of “registered medical practitioner” under Section 2(cc) and to direct the constitution of an inclusive expert committee to review and update the Schedule to the Act in line with contemporary scientific developments and constitutional mandates.

Case Title: Nitin Kumar Upadhyay v. Union of India

Bench: CJI Surya Kant and Justice Joymalya Bagchi

Hearing Date: January 12, 2026