Privileges of Legislature are subject to the provisions of the Constitution; must include rights guaranteed under Part III: Supreme Court

Noting that the Constitution, by itself, does not specify the limitation on the privileges of the Legislature, the top court has held that, indubitably, those privileges are subject to the provisions of the Constitution, which ought to include the rights guaranteed to the citizens under Part III of the Constitution.

The top court has further clarified that such limitations have been predicated in the opening part of Article 194(1) as also in Article 208(1) requiring the House of the Legislature to make rules for regulating its procedure.

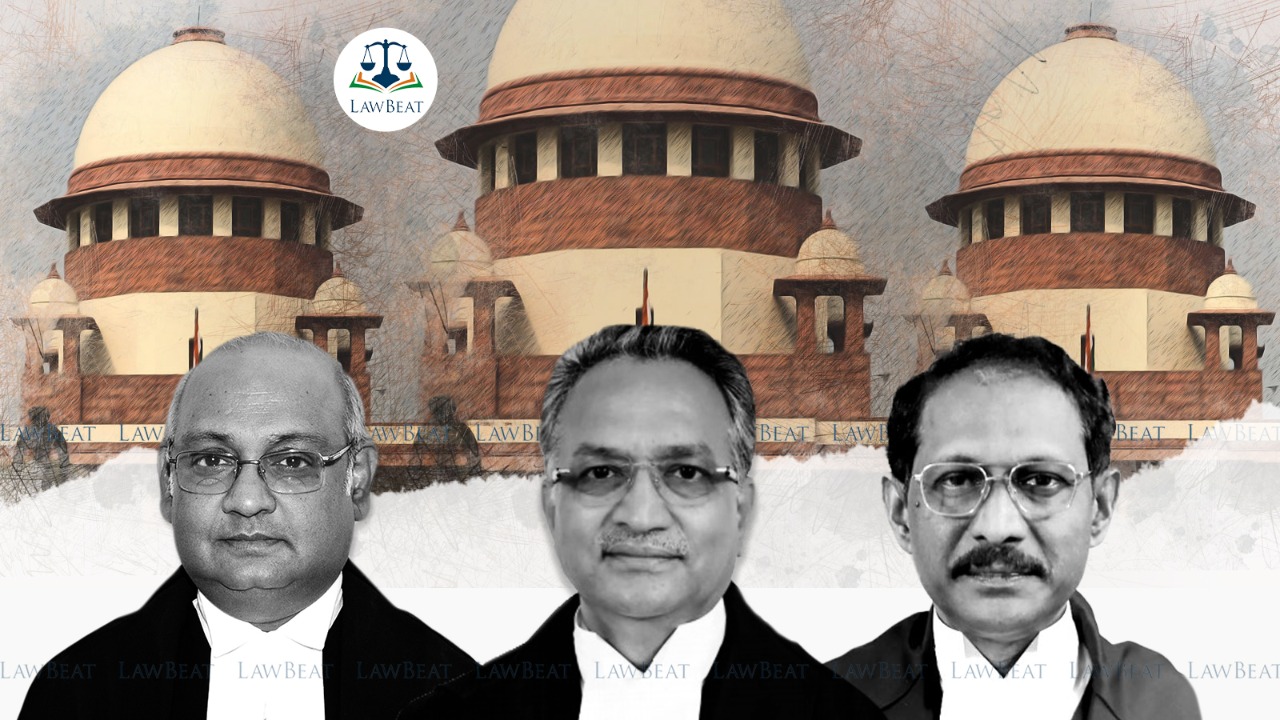

“The moment it is demonstrated that it is a case of infraction of any of the rights under Para III of the Constitution including ascribable to Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution, the exercise of power by the Legislature would be rendered unconstitutional….”, added a bench of Justices AM Khanwilkar, Dinesh Maheshwari and CT Ravikumar.

These observations were made by the top court while dealing with a writ petition filed by 12 BJP MLAs who had challenged an order of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly whereby they were suspended for a period of one year.

Referring to Rule 53 of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly Rules, which gives the power to the Speaker to order withdrawal of member, the court held that the power exercised by the Speaker is a quasi-judicial order and the Speaker is expected to exercise this power only in case of conduct of the member being “grossly disorderly” and in a graded objective manner.

“The raison d’etre is to ensure that the business of the House on the given day or the ongoing Session, as the case may be, can be carried on in an orderly manner and without any disruption owing to misconduct of one or more members", noted the Court.

Referring to the graded (rational and objective standard) approach to be adopted by the Speaker for ensuring orderly conduct of the business of the House, the court said that in the present case, however, the Minister for Parliamentary Affairs introduced a motion in the House for initiating action for contempt of the House, which the Chairman allowed it to be put to vote instantly at 14:40 hours on the same day and it was passed by the House by majority in no time.

It was found that the in the instant case by inflicting suspension for a period “beyond the period necessary” than to ensure smooth working/functioning of the House during the Session “by itself”; and also, as per the underlying objective standard specified in Rule 53, indubitably, suffered from the vice of being grossly irrational measure adopted against the erring member and was also substantively illegal and unconstitutional.

The court further noted that a suspension beyond the remainder period of the ongoing Session was not only a grossly irrational measure, but also violative of basic democratic values owing to unessential deprivation of the member concerned and more importantly, the constituency would remain unrepresented in the Assembly.

As such the bench observed that the one-year suspension was worse than “expulsion”, “disqualification” or “resignation”.

In reference to the motion for initiating action for having committed contempt of the House which ordinarily ought to have proceeded under Part XVIII of the Rules dealing with Privileges, the Court said that this would have required constitution of a Committee of Privileges to enquire into the entire matter by giving opportunity of hearing to the persons concerned.

“Instead of adopting that procedure, the House itself chose to direct withdrawal of the petitioners from the meetings of the Assembly for a period of one year — which direction is neither ascribable to the dispensation prescribed in Part XVIII of the Rules or Rule 53 enabling the Speaker to do so”

The Bench referred to these actions as a substantive illegality and not a case of procedural irregularity.

Resultantly, the Court concluded that the impugned resolution suffered from the vice of being unconstitutional, grossly illegal and irrational to the extent of period of suspension beyond the remainder of the concerned (ongoing) Session.

Further, the court held that it was not a case of mere procedural irregularity committed by the Legislature within the meaning of Article 212(1) of the Constitution.

While allowing the writ petitions and declaring that the impugned resolution directing suspension of the petitioners beyond the period of the remainder of the concerned Monsoon Session held in July 2021 is non est in the eyes of law, nullity, unconstitutional, substantively illegal and irrational, the court ordered thus,

“…the petitioners are entitled for all consequential benefits of being members of the Legislative Assembly, on and after the expiry of the period of the remainder of the concerned Session in July 2021.”

Cause Title: ASHISH SHELAR & ORS. v THE MAHARASHTRA LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY & ANR.