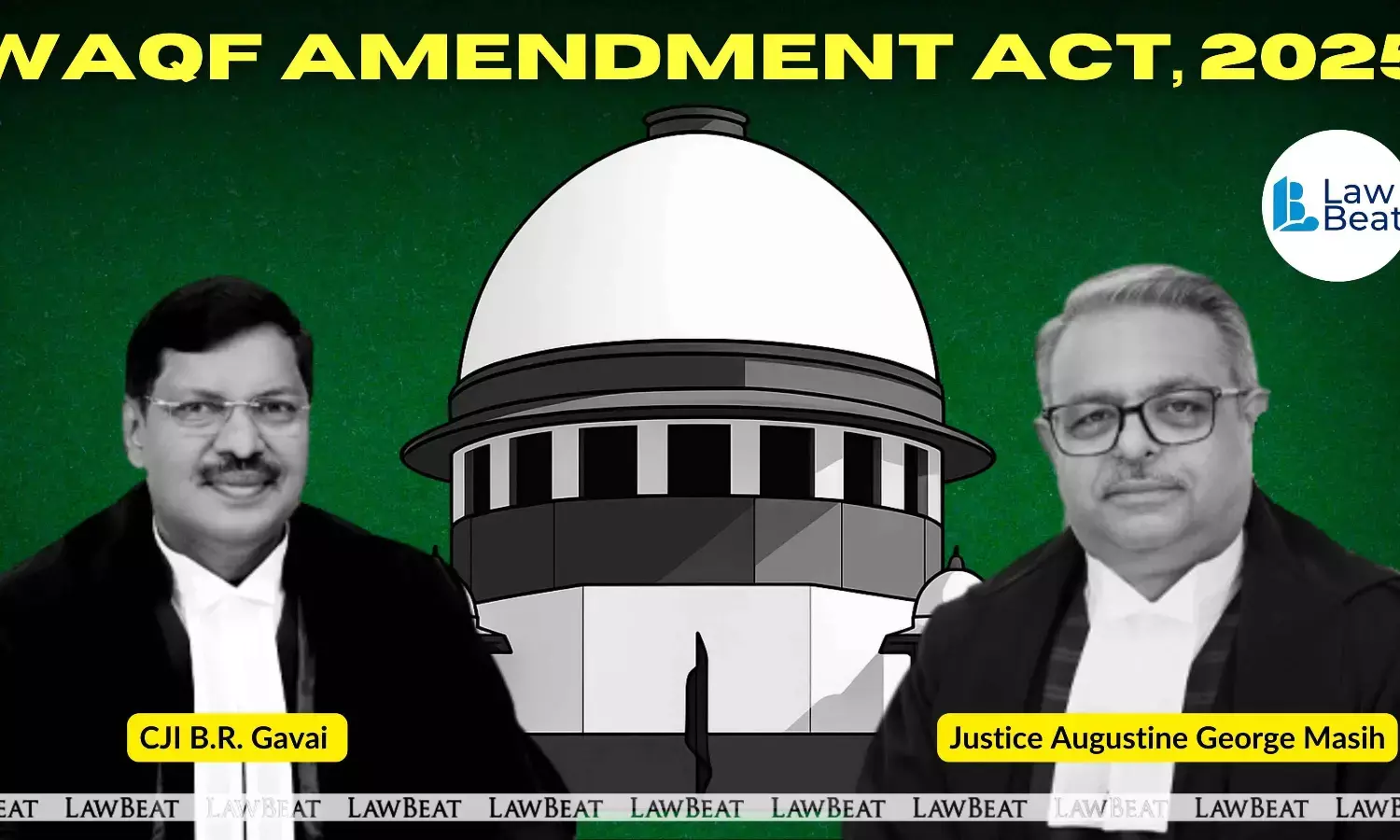

Supreme Court Hears Petitions Challenging Constitutional Validity of Waqf Amendment Act, 2025

The Supreme Court on Tuesday commenced hearing a batch of petitions challenging the constitutional validity of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, for the purpose of interim relief.

Scope of Hearing Disputed

Petitioners Argue ‘Non-Judicial’ Executive Takeover

Legislative History and Registration Debate

Conflict with Ancient Monuments Laws

Additional Constitutional Challenges

Concerns Over Due Process and Judicial Oversight

Presumption of Constitutionality and Interim Relief

Post-Lunch Session

Sibal clarified an earlier reference to the requirement of waqf registration under the 1954 Act, not 1923. He raised serious concerns over the inclusion of protected monuments, such as Jama Masjid and Sambhal, under waqf listings, arguing that once declared protected, such sites lose their original religious character.

He criticised the manner in which Sections 3(D) and 3(E) were introduced in Parliament, without discussion in the Joint Parliamentary Committee and with rules suspended, calling these "deeply disturbing features."

Sibal contended that the 1995 Act had a detailed mechanism for identifying and registering waqf properties, which has now been dismantled. "My right to litigate is lost; my property is taken over without remedy," he submitted. He also highlighted the dilution of Muslim representation in Waqf Boards and argued that religious endowments must be managed by members of the respective faith.

Justice Masih questioned assumptions about non-Muslim majorities, while CJI Gavai sought clarity on statutory roles and composition.

Senior Advocate Rajeev Dhawan criticised the omission of key provisions and argued that the amendments lack proportionality and violate Articles 26 and 29. He cited judgments including Ratilal and T.M.A. Pai, asserting that the Act disregards constitutional safeguards.

Singhvi flagged the arbitrariness of Section 3(r), calling its requirement for proof of practising Islam unconstitutional under Article 15. He further argued that the amendment risks undermining the Places of Worship Act, 1991.

The Centre will begin its defence tomorrow. Hearing to continue on Wednesday.

Previously before Court

It is to be noted, that on May 5, the Supreme Court Bench led by then CJI Sanjiv Khanna had observed that the matter will be heard by a different bench as he was demitting office on May 13.

During the brief proceedings, then CJI Khanna had remarked that the Bench had not delved into the counter affidavit in depth. He had noted that while certain issues around registration and statistics had been raised, “those will require closer scrutiny.” He clarified that he did not intend to pass any interim order or reserve judgment at this stage. “If all parties agree, we can list the matter before a bench led by Justice Gavai on Wednesday,” the CJI had suggested.

The All India Muslim Personal Law Board, in a rejoinder to the preliminary affidavit filed by the Centre, last month have asserted that the recent legislative changes in the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, infringe upon fundamental rights and were passed through a flawed parliamentary process. The Board argued that the Respondents’ defense, that the amendments do not affect essential religious practices, is legally untenable. It stated that compelling the Petitioners to undergo the “Essential Religious Practices” (ERP) test is not only constitutionally misplaced but also ignores the evolution of Indian constitutional jurisprudence.

Last month, the Central Government has submitted a detailed preliminary affidavit before the Supreme Court, defending the constitutional validity of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, and opposing interim reliefs sought by petitioners challenging the law.

About the Bill

Case Title: In Re: The Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025 (1)