‘Rights Cannot Survive Without Duties’: What Legal Luminaries Said at VK 4.0’s Fundamental Rights Session

Legal Luminaries Debate Rights, Duties and Property at VK 4.0 Fundamental Rights Session

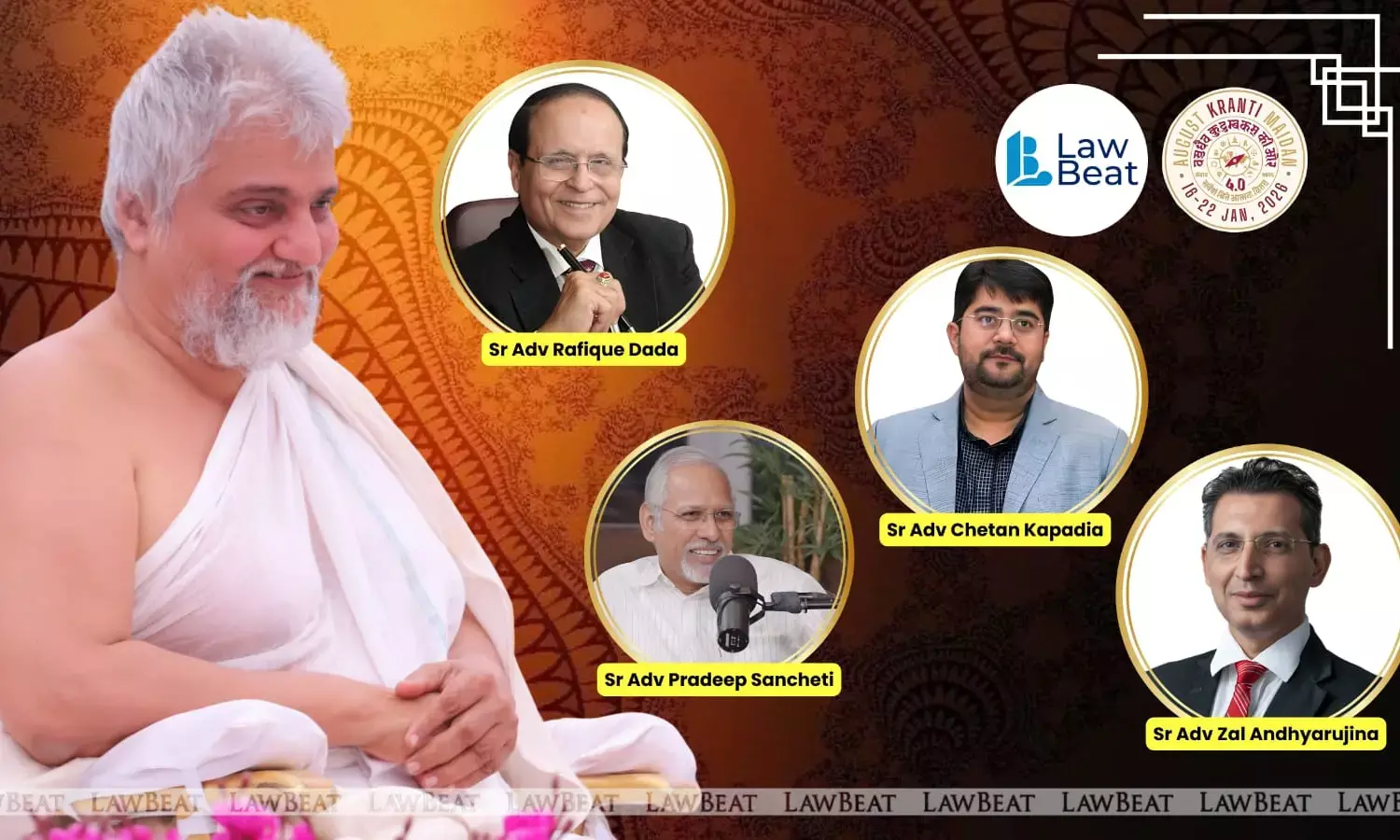

Legal Session 3 of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam Ki Oar 4.0 featured an extensive exchange between senior members of the Bar and spiritual leadership on the meaning and limits of Fundamental Rights in contemporary India.

Opening the discussion, Senior Advocate Rafique Dada reflected on how judicial interpretation has progressively expanded the scope of equality and personal liberty. Referring to constitutional jurisprudence under Article 21, he observed that the extent of liberty recognised by the Constitution is expansive, noting that even a person under a death sentence retains certain facets of liberty. He emphasised that Fundamental Rights and Fundamental Duties are complementary, cautioning against treating rights as standalone entitlements divorced from responsibility.

Dada also addressed the State’s extensive power, particularly in matters of property acquisition, stressing that such power carries a corresponding duty of restraint. He questioned whether development justified displacement in all cases and highlighted concerns surrounding compensation, livelihood and the definition of public good.

Senior Advocate Pradeep Sancheti strongly contested the perceived hierarchy between Fundamental Rights and Fundamental Duties. He argued that duties are not peripheral but foundational, asserting that if citizens act with ethical consciousness, constitutional rights naturally align. Drawing from the idea of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam, he linked environmental degradation and civic neglect to failures of duty rather than deficiencies in constitutional rights. Using examples from public cleanliness and environmental responsibility, he suggested that civic discipline plays a crucial role in sustaining constitutional guarantees.

Moderating the session, Senior Advocate Chetan Kapadia repeatedly pressed the panel on why Fundamental Rights are enforceable while Duties remain largely aspirational. His questions highlighted the constitutional asymmetry between rights and duties and its implications for democratic accountability.

Responding to this, Senior Advocate Zal Andhyarujina traced Fundamental Rights to their origins in natural rights theory, explaining that Part III was intended to protect individuals against State excess. He noted that a substantial portion of India’s constitutional history reflects the judiciary’s role in safeguarding these rights. Describing the Constitution as a living and breathing document, he emphasised that greater focus on individual duty could strengthen institutional resilience.

The discussion was further enriched by His Holiness Yugbhushan Suriji Maharaj, who offered a civilisational perspective on the rights-duties debate. He argued that ancient Indian systems prioritised kartavya over entitlement and that the modern emphasis on rights shaped by Western constitutional models has tilted the balance away from responsibility. He highlighted the intrinsic link between property, livelihood and human dignity, questioning whether development has truly served the public good when displacement remains inadequately compensated.

He also raised concerns about intellectual property regimes, particularly in relation to traditional knowledge, suggesting that modern claims to property must acknowledge historical and communal contributions. Addressing issues of development and brain drain, he pointed to our building infrastructure that the west already serves.

As the session concluded, a shared theme emerged across differing viewpoints: constitutional rights cannot endure through enforcement alone. Whether through judicial protection, civic ethics or institutional restraint, the speakers emphasised that the promise of Fundamental Rights ultimately depends on a collective commitment to constitutional duty.

The second legal session of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam Ki Oar 4.0 - Sankraman Kaal, titled “Nation State Under the Constitution”, turned attention to some of the most enduring and contested questions in Indian constitutional law, particularly the limits of constitutional amendment, the continued operation of Articles 31A, 31B and 31C, and the role of the Basic Structure doctrine in preserving constitutional supremacy.

The first session on "Constitutional Jurisprudence" saw the presence and deliberations by an eminent panel comprising Jamshed Cama, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India; Jayant Jaibhave, Member and Former Chairman of the Bar Council of Maharashtra and Goa and Krishnan Venugopal, Senior Advocate, Supreme Court of India. The discussion opened with a foundational question on the difference between written and unwritten constitutions, and whether codification necessarily leads to better governance. The panel reflected on how a written Constitution like India’s provides certainty, accessibility, and normative clarity in a diverse democracy, while also raising concerns about rigidity in times of social and political change.

Earlier, Senior Advocate and President of the Bombay Bar Association, Shri Nitin Thakker, while speaking at the opening ceremony, invoked Dr. B.R. Ambedkar’s vision of the Constitution as a living instrument. Referring to Dr. Ambedkar’s words, he observed that the Constitution is not a mere lawyer’s document but a vehicle of life whose spirit reflects the spirit of the age