'She became a stumbling block in illicit relationship': SC upholds conviction of man, aunt, uncle for murder of wife

Court noted that the trial court had simply discarded the consistent testimonies of prosecution witnesses as being simply based on presumption; whereas the high court in appeal had extensively dealt with each charge framed against the appellants

The Supreme Court on October 22, 2024, upheld the life sentences for a man and his aunt and uncle for murdering his wife, whom they saw as an obstacle to his incestuous relationship.

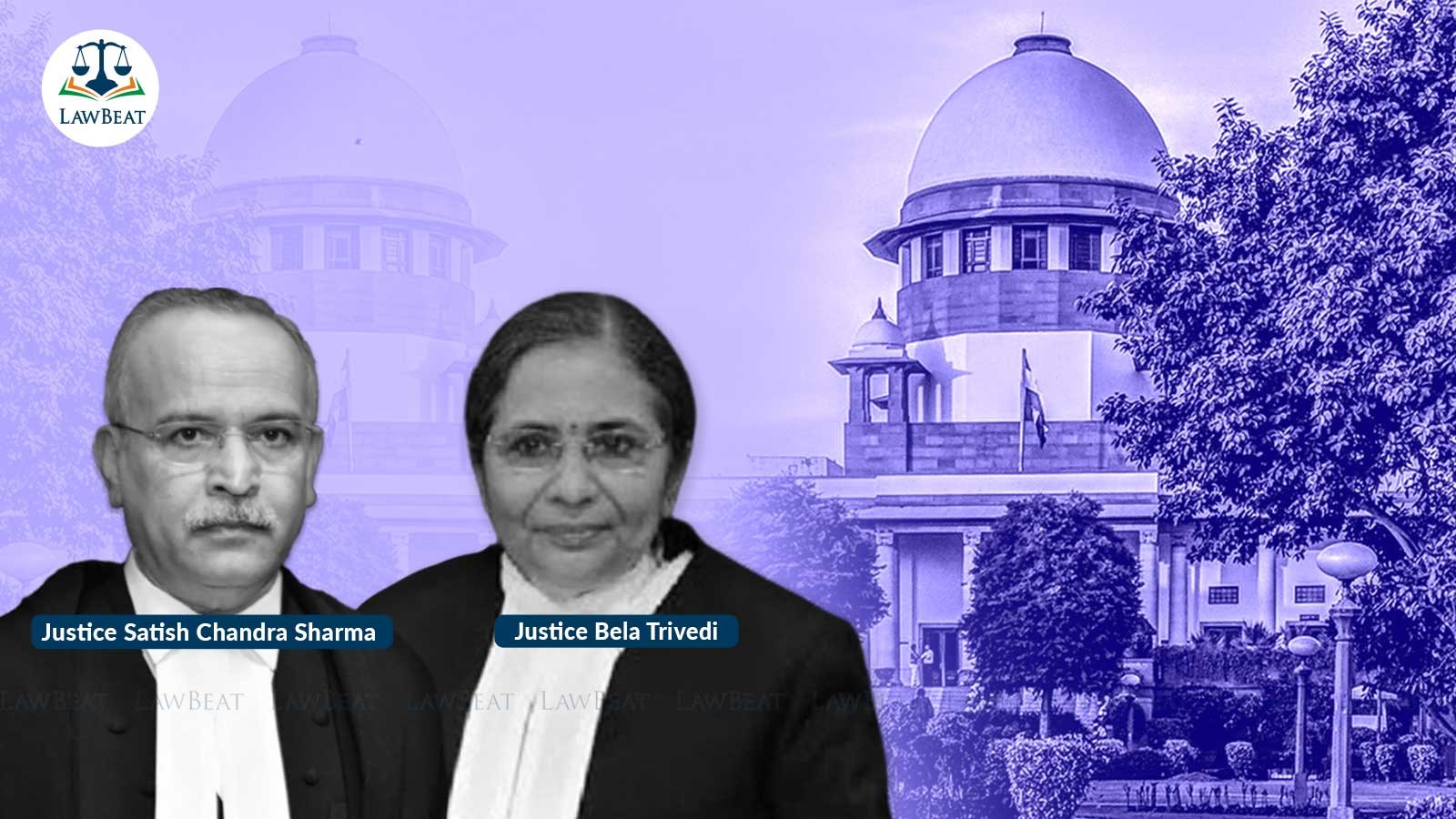

The bench, comprising Justices Bela M. Trivedi and Satish Chandra Sharma, upheld the Madras High Court's decision, which had overturned the acquittal of Uma and others involved in the case.

Court noted the prosecution had proved its case beyond reasonable doubt, established the complete chain of circumstances including the; (i) motive (ii) presence of the appellants at the time of incident (iii) false explanation in the statement under Section 313 of the CrPC (iv) the conduct of the appellants before and after the incident and most pertinently (v) the medical evidence; which in all human probability only correspond to the guilt of the appellants.

Court referred to Sharad Birdhichand Sarda v. State of Maharashtra(1984), which established five guiding principles—known as the "panchsheel of proof"—for evaluating cases based on circumstantial evidence.

The prosecution claimed deceased Rajalakshmi was strangulated to death by the appellants on August 23, 2008, within months of her marriage with accused Ravi due to his illicit relationship with Aunt Uma.

The appellants contended there was no material to establish the alleged story of the father of the deceased; and there was no evidence on record to establish the motive of to murder. They also said that there was nothing on record to establish that the appellants were residing together and were present at the time of occurrence of the said incident.

They contended that the observation made by the high court vis-à-vis the shift of burden of proof under Section 106 CrPC to prove a certain fact, strictly within the knowledge of the appellants was wholly erroneous.

The state counsel said that the trial court did not appreciate the evidence in a proper manner; and consequently, this glaring error led to the acquittal of the accused. He further said the entire set of facts read together with the medical evidence, strictly pointed towards the guilt of the appellants.

The bench noted the case of the prosecution rested on circumstantial evidence, the testimonies of prosecution witnesses read with the reports of medical examination postmortem report and the evidence of the doctors.

Admittedly there are no direct eyewitnesses to the said incident. In such cases, an inference of guilt must be sought to be drawn from a cogently and firmly established chain of circumstances, it said.

The court noted the medical record clearly established that the deceased had died due to several ante mortem external injuries, which could not have been a natural consequence of consuming paint, as alleged by the appellants.

The bench pointed out the presence of the appellants at the time and place of the incident was demonstrable from their conduct before and after the incident.

In their defense under Section 313 CrPC, the appellants had stated that all three of them had gone to Keela Earal to attend a function in the Tractor Company. They returned home only at 6 PM and found the deceased in an unconscious stage and they took her to the hospital.

"Admittedly, the appellants had taken the deceased to the local hospital, however, none of them have been able to establish an alibi at the time of the incident. The silence of the appellants in informing the father or the family of the deceased of her death, also speaks volume of their conduct," the bench said.

The court also pointed out undisputedly, the appellants and the deceased resided together since the marriage of the deceased, which substantiated their presence at the time of occurrence of the incident; and consequently the invocation of Section 106 of the Evidence Act cannot be faulted.

Referring to Trimukh Maroti Kirkan Vs State of Maharashtra, (2006), the bench said, "This court has pointed out that there are two important consequences that play out when an offence is said to have taken place in the privacy of a house, where the accused is said to have been present. Firstly, the standard of proof expected to prove such a case based on circumstantial evidence is lesser than other cases of circumstantial evidence. Secondly, the appellant would be under a duty to explain as to the circumstances that led to the death of the deceased".

"In that sense, there is a limited shifting of the onus of proof. If he remains quiet or offers a false explanation, then such a response would become an additional link in the chain of circumstances. In terms of Section 106 of the Evidence Act, the appellants have not discharged their burden that the injuries sustained by the deceased were not homicidal and not inflicted by them," the bench said.

The court found enough evidence adduced by the prosecution to hold that the appellants had the clear motive to eliminate the deceased.

"An illicit/incestuous relationship between accused No.-1 i.e., Ms Uma and Accused No.-2 i.e., Mr Ravi had become known the deceased Rajalakshmi & her family, and she had become a stumbling block in the relationship, which swelled the common intention of the appellants to murder her," the bench said.

The factum that the deceased passed away within six months of her marriage also becomes a relevant consideration to attribute culpable intent of the appellants, the bench added.

"Although the motive of Balasubramanian (Uma's husband) remains unclear, his aid and assistance in the commission of the crime cannot be ruled out," the bench held.

The court thus opined the prosecution had been able to prove its case beyond reasonable doubt that the accused Nos 1 and 2, with the aid and support of the accused No 3 had murdered the deceased Rajalakshmi and strangulated her to death.

"The collusion and motive of the accused person certainly synthesises with the medical evidence on record, false explanation by the appellants and the entire chain of circumstances, not leaving any link missing for the Appellants to escape from the clutches of justice," the bench said.

The court held that the observation of the trial court that in absence of a direct occurrence witness, motive to commit the crime and the evidence being purely circumstantial in nature, the medical evidence became of less consequences, could not be a fairly plausible view.

It pointed out the trial court had simply discarded the consistent testimonies of prosecution witnesses as being simply based on presumption; whereas the high court in appeal had extensively dealt with each charge framed against the appellants, the grounds on which the acquittal had been based and had dispelled those grounds with reasons.

The bench also explained that it was conscious of the fact that an appellate court must not ordinarily reverse the finding of acquittal, but here the high court had been able to demonstrate perversity and non-appreciation of the materials on record.

"On a fresh appreciation of evidence, we also find ourselves unable to agree with the findings of the trial court and are of the considered view that the circumstances in this case are conclusive and a conclusion of guilt can be drawn," the bench said, dismissing the appeal.

Case Title: Uma & Anr Vs The State Rep by The Deputy Superintendent of Police