Legislature’s Power to Repeal Laws Not Curtailed by Prior SC Rulings: Supreme Court

Merely because the Supreme Court's previous decisions affirmed the constitutional validity of a Statute at the time of its enactment; they do not bind the Legislature from modifying or repealing a statute when subsequent developments warrant a change in policy, court said

The Supreme Court has said that the Legislature, subject to constitutional limitations, may repeal any law it enacts. Court emphasized that the power to legislate on a subject inherently includes the power to repeal the same law.

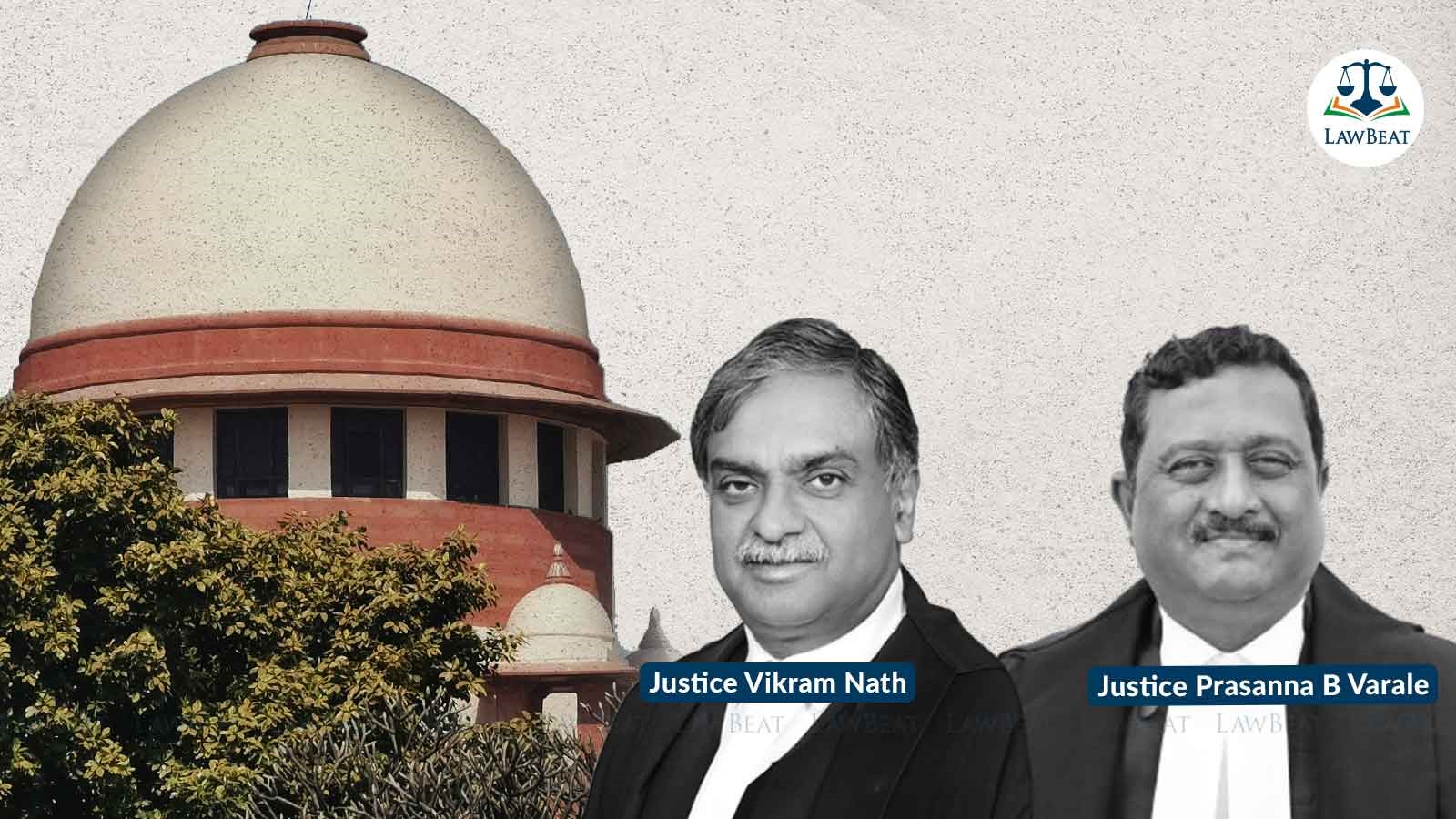

The bench of Justices Vikram Nath and Prasanna B. Varale saidthat merely because the Supreme Court's previous decisions affirmed the constitutional validity of a Statute at the time of its enactment, they do not bind the Legislature from modifying or repealing a statute when subsequent developments warrant a change in policy.

"The power to repeal a law is coextensive with the power to enact it as a repeal statute does not recreate the legal framework anew but rather extinguishes the earlier Act’s operative provisions; it is not subject to the same procedural requirements as an original enactment when it comes to the need for fresh assent, provided that the repeal falls within the legislative competence of the State," the bench said.

Court upheld the validity of Karnataka's 2003 law repealing previous 1976 legislation, which was enacted with the objective of acquiring privately operated contract carriages and bringing them under the control of Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC) to curb their alleged detrimental operation in the State.

Court held that Section 3 of the Karnataka Motor Vehicles Taxation and Certain Other Law (Amendment) Act, 2003, which repeals the Karnataka Contract Carriages (Acquisition) Act, 1976, was constitutional, saying the State Legislature has rightly exercised its power to repeal the Act.

"The rationale underlying the 2003 Repeal Act is sound and consistent with the principles of legislative power. The arguments advanced that the repeal would amount to an impermissible overruling of prior Supreme Court decisions, that it violates the requirement of presidential assent, or that it is otherwise beyond the legislative competence of the State, are untenable," the bench said.

It rejected a contention by the KSRTC that repealing the KCCA Act was unconstitutional because it effectively overruled the previous decisions of the Supreme Court, which upheld the validity of the 1976 law.

Finding that the argument failed to recognise the dynamic nature of legislative policy, the bench said, "Those Supreme Court decisions merely affirmed the constitutional validity of the KCCA Act at the time of its enactment; they do not bind the Legislature from modifying or repealing a statute when subsequent developments warrant a change in policy".

Holding the argument that the repeal should have required fresh presidential assent as misplaced, the bench said, "A repeal statute does not recreate the legal framework anew but rather extinguishes the earlier Act’s operative provisions; it is not subject to the same procedural requirements as an original enactment when it comes to the need for fresh assent, provided that the repeal falls within the legislative competence of the State".

The bench declared that the repeal of the KCCA Act was "a deliberate policy decision aimed at fostering a more dynamic and responsive transport framework rather than an attempt to nullify well-established judicial pronouncements".

Court also confirmed that the Secretary of the State Transport Authority is empowered to grant non-stage carriage permits (including contract carriage, special, tourist, and temporary permits) in accordance with Section 68(5) of the MV Act and Rule 56(1)(d) of the KMV Rules, subject to the limitations and conditions. It said quasi-judicial functions may be delegated if the enabling statute expressly provides for such delegation.

"The State Transport Authority (STA) possesses the power to delegate its functions under Section 68(5) of the MV Act, as expressly provided by the statute and further clarified by Rule 56(1)(d) of the KMV Rules. The delegation is a rational and necessary administrative measure that facilitates prompt and efficient processing of permit applications without undermining the oversight function of the STA," the bench said.

Dismissing an appeal filed by the KSRTC against the March 28, 2011 judgment of the Karnataka High Court, the apex court held that the repeal was not an arbitrary act of legislative whim as it was backed by a clear statement of objects and reasons that identified the deficiencies in the existing regulatory framework and the necessity to liberalise the transport sector.

It noted that the intention was to dismantle the statutory monopoly that the KCCA Act had created for the KSRTC and to open the door for private operators to address the burgeoning public transport needs.

The bench said the contemporary challenges, such as increasing demand for public transport services, congestion in urban areas, and the need for efficient service delivery, necessitated a more flexible regulatory regime.

The bench agreed with the Karnataka High Court's division bench judgment that the Repeal Act was rooted in the practical realities of modern transport policy. It, however, overturned the High Court's ruling that prohibited delegation of permit-granting powers to the Secretary, State Transport Authority.

The court held the high court’s reasoning on the non-delegability of permit-granting power as flawed.

"The practical impact of not allowing delegation would be to overload the STA with routine functions, potentially causing undue delays and inefficiencies in the permit-issuance process. Such delays could disrupt the balance of public transport service delivery, which the Legislature clearly sought to improve by liberalizing the regime for non-stage carriage permits. In this light, the delegation of routine permit-granting powers is not only legally permissible but is also necessary to meet the practical demands of an evolving transport sector," the bench said.

The top court noted that the legislative history and the Statement of Objects and Reasons attached to the 2003 Repeal Act made it clear that the Legislature intended to remedy the inefficiencies of the past by introducing competition into the transport sector.

Case Title: M/s S R S Travels By Its Proprietor K T Rajashekar Vs The Karnataka State Road Transport Corporation Workers & Ors